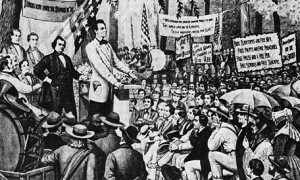

Yesterday was the 153rd anniversary of the Lincoln-Douglas debate at Galesburg — October 7, 1858, the fifth of the seven debates the two men had between August and October that year. To me, it is the finest of the debates to read, and I highly recommend sitting down with its full text.

Yesterday was the 153rd anniversary of the Lincoln-Douglas debate at Galesburg — October 7, 1858, the fifth of the seven debates the two men had between August and October that year. To me, it is the finest of the debates to read, and I highly recommend sitting down with its full text.

Douglas and Lincoln represented something of the center right and center left of northern opinion on slavery in 1858; Lincoln a clear anti-slavery man but far from an abolitionist, Douglas personally opposed to slavery and far from a friend to the south, but completely opposed to any anti-slavery movement that might threaten the union and fundamentally against the idea of one state telling another how to mange its internal affairs in a federal union. In the debate, each sought to attack the weakness of the other’s position by promoting their own. And listening to each reckon with the moral aspect of slavery and the seriousness of the threat to the union, all within the context of a political-electoral speech, is undeniably moving.

The Lincoln-Douglas debates were set up with one man speaking for 60 minutes, the other for 90, and then the first again for 30. They took turns going first; in Galesburg, Douglas went first. The most interesting part of his speech, for me, was when he emphatically derided the rise of the Republican Party. Over 100 years after the war ended, in his incredible history of the 1850’s, David Potter wrote about the metamorphosis of the political parties:

If Calhoun had been alive to witness [the 1856 election], he might have observed a further snapping of the cords of Union [that he spoke about in 1850]. The Whig cord has snapped between 1852 and 1856, and the Democratic cord had been drawn very taut by the sectional distortion of the party’s geographical equilibrium. It could not stand much more tension without snapping also. As for the Republican party, it claimed to be the only one that asserted nationalist principles, but it was totally sectional in its constituency, with no pretense to bisectionalism, and it could not be regarded as a cord of union at all.

Douglas, speaking first at Galesburg, made much the same point:

Now, let me ask you whether the country has any interest in sustaining this organization known as the Republican party. That party is unlike all other political organizations in this country. All other parties have been national in their character — have avowed their principles alike in the slave and free States, in Kentucky as well as Illinois, in Louisiana as well as in Massachusetts. Such was the case with the Old Whig party, and such was and is the case with the Democratic party. Whigs and Democrats could proclaim their principles boldly and fearlessly in the North and in the South, in the East and in the West, wherever the Constitution ruled and the American flag waved over American soil.

But now you have a sectional organization, a party which appeals to the Northern section of the Union against the Southern, a party which appeals to Northern passion, Northern pride, Northern ambition, and Northern prejudices, against Southern people, the Southern States, and Southern institutions. The leaders of that party hope that they will be able to unite the Northern States in one great sectional party, and inasmuch as the North is the stronger section, that they will thus be enabled to outvote, conquer, govern, and control the South. Hence you find that they now make speeches advocating principles and measures which cannot be defended in any slave-holding State of this Union, Is there a Republican residing in Galesburg who can travel into Kentucky, and carry his principles with him across the Ohio? What Republican from Massachusetts can visit the Old Dominion without leaving his principles behind him when he crosses Mason’s and Dixon’s line? Permit me to say to you in perfect good humor, but in all sincerity, that no political creed is sound which cannot be proclaimed fearlessly in every State of this Union where the Federal Constitution is the supreme law of the land.

When Lincoln spoke, he did not address this political concern directly. But I love this section, which touches the idea:

The judge tells us, in proceeding, that he is opposed to making any odious distinctions between free and slave States. I am altogether unaware that the Republicans are in favor of making any odious distinctions between the free and slave States. But there still is a difference, I think, between Judge Douglas and the Republicans in this. I suppose that the real reference between Judge Douglas and his friends and the Republicans, on the contrary, is that the judge is not in favor of making any difference between slavery and liberty — that he is in favor of eradicating, of pressing out of view, the questions of preference in this country for free or slave institutions; and consequently every sentiment he utters discards the idea that there is any wrong in slavery. Everything that emanates from him or his coadjutors in their course of policy carefully excludes the thought that there is anything wrong in slavery. All their arguments, if you will consider them, will be seen to exclude the thought that there is anything whatever wrong in slavery. If you will take the judge’s speeches, and select the short and pointed sentences expressed by him, — as his declaration that he “don’t care whether slavery is voted up or down,” — you will see at once that this is perfectly logical, if you do not admit that slavery is wrong. If you do admit that it is wrong, Judge Douglas cannot logically say he don’t care whether a wrong is voted up or voted down. Judge Douglas declares that if any community wants slavery they have a right to have it. He can say that logically, if he says that there is no wrong in slavery; but if you admit that there is a wrong in it, he cannot logically say that anybody has a right to do wrong.

He insists that, upon the score of equality, the owners of slaves and owners of property — of horses and every other sort of property — should be alike, and hold them alike in a new Territory. That is perfectly logical, if the two species of property are alike, and are equally founded in right. But if you admit that one of them is wrong, you cannot institute any equality between right and wrong. And from this difference of sentiment — the belief on the part of one that the institution is wrong, and a policy springing from that belief which looks to the arrest of the enlargement of that wrong; and this other sentiment, that it is no wrong, and a policy sprung from that sentiment which will tolerate no idea of preventing that wrong from growing larger, and looks to there never being an end of it through all the existence of things — arises the real difference between Judge Douglas and his friends on the one hand, and the Republicans on the other. Now, I confess myself as belonging to that class in the country who contemplate slavery as a moral, social, and political evil, having due regard for its actual existence amongst us, and the difficulties of getting rid of it in any satisfactory way, and to all the constitutional obligations which have been thrown about it; but who, nevertheless, desire a policy that looks to the prevention of it as a wrong, and looks hopefully to the time when as a wrong it may come to an end.

The contrast is striking, especially since Douglas and Lincoln are both northerners and both are happy that there is no slavery in Illinois. They are, in the big picture, on the same side. At least relative to the southerners. This should give you some idea of how difficult the abolitionists had it, and how much variety of opinion existed in the north, even when you excluded the pro-southern doughfaces (which, of course, some counted Douglas among prior to his fallout with the Buchanan administration over Kansas) and the outright pro-slavery northerners.

The Lincoln-Douglas debates are also important because of the implicit structural commentary they provide. As I’ve written about before, they are the most important example of why the 17th amendment was necessary, and why it shouldn’t be repealed, especially if you value federalism: these “races” for Senate were distorting state elections. This is one of the dirty little secrets of the 19th century. Lincoln and Douglas were running for the U.S. Senate, but they weren’t actually running; the voters listening to those debates were only going to be allowed to vote for the state legislature (and U.S. House, of course), which in turn would select Lincoln (if the Republicans had control) or Douglas (as it happened, when the Democrats won control).

See the potential problem? In an election ostensibly for state officials, many voters were making their decision based on the consequences for the national government. This accelerated in the later 19th century, to the point where state-level candidates were sometimes nothing more than pass-throughs for a Senate vote. Except that they got to run the state government for the next two years. That’s not good if you are interested in federalism, and I don’t think it’s good in a democracy, in general. By switching to a direct vote system, not only was the Senate made a more directly democratic body, but state elections were freed from the yoke of Senate elections, allowing citizens greater freedom of personal choice when picking their state representatives.