Newt Gingrich , 12/19/11

Jon Huntsman, Jr., 12/20/11

Willard Mitt Romney, 12/21/11

Michele Bachmann, 12/22/11

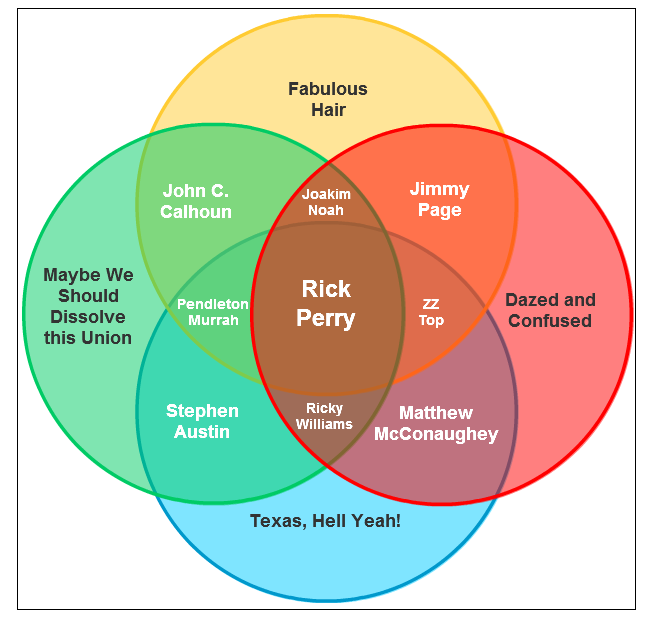

Rick Perry, 12/23/11

Herman Cain, 12/25/11

Rick Santorum, 12/28/11

Newt Gingrich , 12/19/11

Jon Huntsman, Jr., 12/20/11

Willard Mitt Romney, 12/21/11

Michele Bachmann, 12/22/11

Rick Perry, 12/23/11

Herman Cain, 12/25/11

Rick Santorum, 12/28/11

Newt Gingrich , 12/19/11

Jon Huntsman, Jr., 12/20/11

Willard Mitt Romney, 12/21/11

Michele Bachmann, 12/22/11

Rick Perry, 12/23/11

Herman Cain, 12/25/11

Ron Paul, 12/31/11

I’m reasonably confident (i.e. I’ll lay you 30-1 or 40-1, i.e. I think there’s a 97%+ chance) that Mitt Romney is going to be the 2012 GOP nominee for President. Now, I could be wildly wrong in my estimation. And regardless of whether Romney wins or not, we’ll never know for sure. Unless you assign a 100% or 0% chance of something occurring, any observable single-trial result will plausibly conform to your estimation.

So leave that aside.What I want to talk about here is why the race appears so much tighter than that. And the reason is simple: virtually everyone involved has an incentive to portray the race as still wide open. Let’s take a look:

1. The media. This is the most obviously biased actor. Uncertainty is the press’ best friend in elections. You can’t sell advertising during debates that no one wants to watch, and no one wants to watch a debate for a race that is over. Ditto for election night coverage in individual primary states. No one is going to watch the returns if there is only one competitive candidate. So political news ratings/sales will be higher if the horse-race continues until late spring or (god help us) to the convention (which it won’t). Therefore, the press has every reason to play up the competitiveness of the race, even after everyone else has more or less conceded it is over.

2. The Democrats. President Obama and other political opponents obviously have an interest in the GOP primary actually being drawn out, because it would sap the collective resources of the candidates. But Democrats also have an incentive to portray the race as competitive even if it is not, for at least three reasons. First, it ties the reasonable and stronger candidates (like Romney) to the unreasonable and unelectable candidates. If GOP voters can’t choose between Mitt Romney and Ron Paul, then it might reason that Romney is similar to Paul, or that GOP voters think they are both reasonable candidates, or both. Second, it fosters the belief that GOP voters don’t really like their best candidates, or that the party is caught in some sort of civil war. Either of those beliefs might turn off moderate voters. Finally, there’s the plausible meta-possibility that pretending an election is close may actually make it closer, or at least draw it out (but more on this later.)

3. Iowa and New Hampshire. If the race were over and everyone knew it, then there would be a lot of downsides for the early primary states. Candidates wouldn’t be visiting constantly and making promises, local politicians wouldn’t have the chance to appear with candidates and make endorsements, and local media wouldn’t be able to host debates, sell advertising, and make more money. I mean, you don’t see President Obama prancing around Iowa and New Hampshire non-stop for the Democratic nomination, do you? One of the advantages of going first in the sequential primaries is to have leverage in choose between competitive candidates. But a second reason is to extract promises from whoever ends up winning the nomination, and that’s a whole lot easier if the race appears competitive.

4. Later Primary States. Same logic applies here as above. Many of the benefits of holding a primary are only conferred if the primary is competitive. But again, that threshold is met not by the race being undecided, but by the appearance of the race being possibly undecided.

5. Pollsters. There was a long (and wonderful) nerdfight earlier this year on the internet over the relative importance of polling and fundamentals in predicting the outcome of elections. My personal opinion is that in primaries, both are relevant, but fundamentals are more important. Others disagree. But anyone who throws the lion’s lot with polling needs to believe that the race is still at least somewhat competitive, because Romney doesn’t have anything near a majority in the national polls, and can be found to be losing in state polls in Iowa. If the race is over right now, then the polls are rendered very blunt instruments of analysis.

6. The non-Romney candidates. The basic link here is resources. If the race is over and everyone knows it, you will not be receiving much in the way of donations, volunteers, endorsements, or anything else that can help you win. That’s probably also true if you have less than a 2% chance and everyone knows it. But what if you have a 2% chance and everyone thinks you have a 25% chance? Now that’s a situation you might want to create. Sure, you’re still a longshot. But at least you will have a compelling answer on the phone when someone wants to know why they should give you $2000.

7. Romney. At first glance, this seems ridiculous. And on one level, it is: if Romney has a 85% chance of winning, he might be better off convincing everyone that he has a 100% chance of winning, which would dry up his opponents fundraising and give him that last 15%, which would plausibly allow him to turn his attention to the general election and begin his pivot.

But what if Romney does indeed have a 98% or 100% chance of winning the nomination right now, he knows it, but everyone else (see above) is pretending it’s not true? He can’t just go out and say it or act on it in any way, because he could conceivably hurt himself. No voters want to hear it, everyone else would be denying it, and he would sound arrogant. So at the bare minimum, Romney has to play along with the competitiveness thing for now.

But he also has to consider resources. The primaries are an excellent opportunity to mobilize volunteers in various states, gather data like phone numbers, expand your fundraising base, and get people excited. A continued primary season aids this; by the time you get to the last primaries, it’s not really possibly to mobilize and activate a large cadre of volunteers. Now, at some point (rather early, I would say) the benefits of turning to the general election outweigh the benefits of being able to highly mobilize resources in sequential primary states. But that doesn’t happen, I don’t think, until after all the other actors stop pretending the primaries aren’t over. And so at least until then, Mitt has the incentives, just as they do, to publicly see this thing as a race.

8. Political Junkies. You really think my wife would put up with me talking and writing about this endlessly if I admitted it was over?

Newt Gingrich , 12/19/11

Jon Huntsman, Jr., 12/20/11

Willard Mitt Romney, 12/21/11

Michele Bachmann, 12/22/11

Rick Perry, 12/23/11

Rick Santorum, 12/28/11

Ron Paul, 12/31/11

A quick word on Ron Paul, then some links and my schedule next week.

Given all the stuff that’s come out over the past few days — and it’s just way too much to link to, just get on the internet or twitter and open a few doors — I don’t think any libertarian in good conscience can continue to support Paul as a candidate in any capacity. I certainly can’t. There’s no reasonable doubt left that Paul willfully lent his name to some mixture of very ugly segregationist thought crossed with the conspiratorial ideology of an anti-government militia man. Now, people can change (i.e. Bobby Byrd) and you can associate with ugliness for the greater good (i.e. northern Democrats during the 20th c.), and those sorts of rationalizations are fine as far as they go. But I’m not running a party and Ron Paul’s not a serious candidate. So I’m done with him. I was probably going to vote for Gary Johnson in the general anyway. So that’s fine.

But that doesn’t mean there’s not room for regret. All this makes me very sad for what could have been. For all the grave-dancing going on around the Internet right now by liberals and conservatives alike, I’m not afraid to say that the discrediting of Paul comes with some very serious negatives for the Republican party and for America. He was more or less the only person on the debate stage this year who cared one bit about civil liberties or the prospect of reversing the unsustainable American empire. And for voicing that, I’m grateful to him. To the degree that his positions on those issues are marginalized, and to the degree that Romney and Gingrich and whoever else is left do not have to grapple with them, it’s our loss.

I thought Jonathan Bernstein had a nice take on why different people support Paul, and what the revelation of these newsletters means for those people. I definitely fall into the camp that thought of him not as a serious candidate, but as a positive force in the party and a protest vote against what I believe is a conservative ideology gone off the rails. Needless to say, his economics were beyond kooky and many of his positions too extreme for my pragmatic libertarianism, but I admired his foreign policy honesty and loved his civil liberties stances. It’s the endless frustration of a thinking libertarian to have to deal with racists and conspiracy theorists and plain old crackpots. How we have now gone 10 years down the post-9/11 road and still haven’t been able to find a libertarian politician who can credibly fight for the mantle in either party makes me shudder that it might not be possible. And so we’ll keep waiting. For who, I do not know.

But I do know that it will never be Ron Paul.

Anyway, here are a few links from my reading this week:

I haven’t really written on the payroll tax battle per se, and that’s because there are just a million good takes things to read. I suggest starting with Sullivan’s roundup, and branching out from there.

Here’s my old grad school friend Tom Pepinksy on exogenous variation in comparative politics.

Polls is magic, says Roger Simon. You are a moron, says Seth Masket. John Sides agrees.

Here’s a libertarian cause that is uniting the conservatives and liberals: stopping SOPA.

Matt Yglesias asks why we subsidize college at all, rather than just make transfer payments to the poor. Good point.

Kevin Drum looks at the disaster that was the LA school district trying to get rid of junk food in the lunch room.

Blogging will be spotty over the next week — we’re headed up to northern New York for Christmas — but I’ll definitely post the remaining entries in the GOP Candidate Venn Diagrams series, and probably a few other items. Happy Holidays to all and safe travels.

Newt Gingrich , 12/19/11

Jon Huntsman, Jr., 12/20/11

Willard Mitt Romney, 12/21/11

Michele Bachmann, 12/22/11

Herman Cain, 12/25/11

Rick Santorum, 12/28/11

Ron Paul, 12/31/11

Newt Gingrich , 12/19/11

Jon Huntsman, Jr., 12/20/11

Willard Mitt Romney, 12/21/11

Rick Perry, 12/23/11

Herman Cain, 12/25/11

Rick Santorum, 12/28/11

Ron Paul, 12/31/11

“The Republicans? They’re just the opposition. The Senate is the enemy.”

-variously attributed (usually to former Speaker Tip O’neil)

There’s really nothing quite like a good inter-chamber standoff on the Hill. Most of the time, I think, inter-chamber conflict is overstated; many of the disputes are partisan rather than chamber, and the chamber leaders tend to have good bargaining relationships. But when things break down, they can really break down. And that’s when you can start seeing some real fireworks, as staffers speak their minds and/or defend their respective institutions.

Now, the current politics of the payroll tax — with the House Democrats and most of the Senate pitted against most of the House Republicans — isn’t a strictly House vs. Senate issue. A classic inter-chamber fight would have the same party in control of both House and Senate, mitigating the partisan dimension. And we’re nowhere near the inter-chamber acrimony of the early 90’s. But many of the underlying structural and institutional factors that create classic chamber disputes are visible here, and thus it’s worth reviewing what exactly those factors are. To wit: why do two legislatures, democratically-elected by the same nation, regularly not see eye-to-eye on public policy?

Let’s break the factors into three categories: structural, institutional, and social-cultural.

Structural Factors

1. Different Member time horizons. Representatives face re-election every two years; Senators every six. As the Founders well-knew when they intentionally created this arrangement, this would put the Representatives much closer to the short-term passions of the voters, in two ways: first, new Representatives would be elected in response to temporary popular passions, while those same passions would pass over Senators not up for election; second, existing Representatives would need to more closely monitor, relative to Senators, the temporary popular passions of the people as they considered how to beset represent their constituents. Representatives are, on average, more attentive than Senators to short-term constituent positions and concerns. They tend to go home more often, they are less likely to reside in Washington, and the often dedicate a larger percentage of staff to constituent relations.

2. Different electoral cycles. This follows from the time horizons, but isn’t always appreciated. All of the Representatives are up for election next year, but only 1/3 of the Senate seats will be contested. Neither of those facts are products of the length of the term; we could elect half of the membership of the House each year, and we could elect all Senators every six years. There are two upshots to the existing arrangement. The first is compositional: only 1/3 of the Senate is composed of people elected in 2010, but the entire House was elected then, including a sizeable number of freshmen. The second aspect is prospective: every Representative will stand election next fall, and waiting for each of them will be an opponent who is both cognizant — and constitutive — of the prevailing popular passions. Not every Senator will face that test. And the entire Senate will never face that test at the same time.

3. Different constituencies. This is more or less self-explanatory, but there are a couple of sub-points here. First, there’s the Madisonian idea of larger constituencies producing more moderate Members, due to localized extremism that is washed out in aggregation. But there’s also the question of district construction in the House — i.e. gerrymandering — that is not a factor in the Senate. House districts drawn to protect incumbents may end up producing more ideologically extreme Members on both sides, while still tending to wash out the vote at the statewide Senate level.

The Founders institutional solutions for their normative desires didn’t always work out, but these, for the most part, did. The famous analogy is the Senate as the “cooling saucer” for the “hot tea” produced in the House, which is allegedly how Washington explained the chambers to Jefferson upon his return from France, having missed the Constitutional Convention. As Madison wrote in his convention notes, “the use of the Senate is to consist in its proceedings with more coolness, with more system and with more wisdom, than the popular branch.” One intriguing aspect of this that is relevant right now is that the “Senate as saucer” theory implies House action and Senate resistance, which naturally fits with the inertia of the federal legislative process. But Madison doesn’t contemplate the opposite: Senate demands for action and House resistance. What happens when the hot tea has the inertia of inaction on its side?

Institutional Factors

1. Majoritarianism vs. consensus. The Rules of the House and the Rules of the Senate strongly influence policy outcomes in each chamber. Most people are now familiar with the key difference: the House is structured to allow a majority to work its will; the Senate is structured as to require supermajority consensus for positive action. This goes beyond the issue of the filibuster in the Senate. For example, House rules allow the majority to easily alter the rules, which in turn makes controlling the amendment process quite trivial. In the Senate, on the other hand, special rules cannot be written by the majority, meaning that the amendment process is usually negotiated by unanimous consent, which gives the minority much more leverage over the substance of the deliberations.

2. Leadership power. While it’s true that the power of the leadership ebbs and flows over time in the House, in general the backbench Representatives have less individual institutional power in the House than in the Senate. Part of this is simply a numbers game: less Senators means greater opportunity for less senior Members to hold powerful committee slots. But it’s also a product of the rules (for example, consider how important unanimous consent agreements are), the structural features of the chamber (i.e. staggered time-horizons) and the chamber culture. The party caucuses in the House usually have an easier time keeping their backbenchers in line, and they can usually afford to lose a few. In recent decades, this has grown more stark, as leadership power has increased in the House while decentralization has perhaps individual power in the Senate.

Remember, these factors are independent of the structural factors. Even if both chambers were composed of Members chosen by identical electoral systems, these factors would create a situation in which the partisan majority in the House could routinely pass its legislative agenda in a pretty clean form, while the Senate would need to accommodate wider points of view, if it could pass the legislative agenda at all.

Social-Cultural Factors

1. Citizen perception. It may be the case that citizens have different preferences for Representatives and Senators. That is, an individual voter might choose one candidate for House, but would not choose the same candidate for the Senate. I don’t have any empirical evidence for this (though it probably exists), but there’s an easy theoretical circumstantial case to be made: the Senate has a set of responsibilities that the House does not have — judicial and executive branch nominations; treaty ratification — and voters might weigh these responsibilities when assessing candidates. If this is the case, then you might find that, independent of structural and institutional factors, Representatives and Senators elected by identical constituencies might not agree on policy, if those policy disagreements correlate with voter choice discrepancies for the respective offices.

2. Chamber patriotism. There’s an old joke on the House side of the Capitol that involves a Representative winning election to the Senate. It varies in its telling, but the punch line is always and now the average IQ of both chambers has increased. It’s a joke that can be retold often: historically, about 30-40% of Senators in any given Congress had previously served in the House. Of course, as I wrote in this blog post, the joke is hardly ever told on the North side of the Capitol; the number of Senators who go on to serve in the House is very small. The last Representative to have previously served in the Senate was Claude Pepper, who served in the Senate from 1936 until 1951, and in the House from 1963 until 1989.

What independent effect might this have? It’s just speculation, but my guess is that in a situation where you have two aggregate groups that are ostensibly equals in terms of power, but are structurally designed such that most individuals would prefer to be in one rather than the other and that virtually all individuals who change groups go one direction, you are bound to occasionally end up with the dual emotions/feelings of superiority and jealousy. And those two feelings can be powerful players in political outcomes, independent of the structural and institutional factors that gave rise to them.

Newt Gingrich, 12/19/11

Jon Huntsman, Jr., 12/20/11

Michele Bachmann, 12/22/11

Rick Perry, 12/23/11

Herman Cain, 12/25/11

Rick Santorum, 12/28/11

Ron Paul, 12/31/11

A few interesting things on the House floor today:

1. The House adopted a special rule today (H.Res.502; here is the committee report from the Rules Committee) to take up the Senate amendment to the payroll tax bill and to disagree with the amendment and propose a conference. Last week, I brought the full-court geekery explaining special rule layover waivers and the special rule process in general. H.Res.502 is a nice compliment to that discussion: section 5 of the rule specifically waives the chamber rule requiring a two-thirds vote to consider a special rule on the same legislative day it is reported from the Rules Committee from now until January 15th, which is two days before the second session of the 112th Congress is scheduled to start.

Since the House was originally scheduled to close the 1st session of the 112th this week and is unlikely to take up major legislation other than the payroll tax and related items, the waiver more or less gives the House flexibility to act quickly on such deals between now and the start of the second session. As noted last week, the chamber rules allow same day consideration in the last days of a session, but that provision is often ineffective since (as is the current situation) the the session adjournment date is rarely known in advance.

2. I thought Jordan Ragusa’s post today regarding the House move to reject the Senate amendments and propose a conference was quite good (although I mildly disagree that the conferees matter much in this situation; they are almost certainly just proxies for the chamber leaders). Steve Benen was a bit annoyed this morning about the procedural method that the House was using to take up the issue, but, as Jordan points out, it wasn’t an unusual procedural action. Is the politics frustrating? Sure. But are the tactics some sort of convoluted invention? Not at all.

3. Representative Edwards (D-MD) raised a question of privileges of the House and offered a resolution (H.Res.504) disapproving of comments Representative West (R-FL) made earlier this week about the Democratic Party. Such a motion is privileged for consideration but only requires immediate action by the chair on the matter if it is offered by the majority leader or minority leader. When offered by anyone else, the chair can postpone ruling on whether the resolution qualifies for consideration under the chamber rules for two days. The chair did postpone, but only until after the debate on H.Res.501. Upon taking up the question of privileges again, the chair ruled that it did qualify, and the resolution was read in full by the clerk. Debate on the resolution then proceeded under the one-hour rule. Representative Price (R-GA), however, immediately moved to table the resolution, and the motion to table was agreed to, which kills the resolution.

4. A lively colloquy was held between Minority Leader Hoyer (D-MD) and Majority Leader Cantor (R-VA). A colloquy is nothing more than a back and forth discussion between two or more Members, accomplished procedurally in the House by a Member gaining the floor for some period of time and then yielding to the other Member as necessary for discussion. The floor leaders regularly have a colloquy at the end of a workweek to discuss the upcoming schedule, but today was different because the colloquy occurred in the middle of a series of votes, which meant that most of the House membership was in attendance for it. This led to some cheering and mild booing as the leaders discussed the upcoming schedule.

Newt Gingrich , 12/19/11

Mitt Romney, 12/21/11

Michele Bachmann, 12/22/11

Rick Perry, 12/23/11

Herman Cain, 12/25/11

Rick Santorum, 12/28/11

Ron Paul, 12/31/11

Jon Huntsman, 12/20/11

Mitt Romney, 12/21/11

Michele Bachmann, 12/22/11

Rick Perry, 12/23/11

Herman Cain, 12/25/11

Rick Santorum, 12/28/11

Ron Paul, 12/31/11

John Sides and friends on whether or not GOP primary voters care about electability.

Seth Masket explains why all the cultural-divide-predicts-election stories are worthless. Jordan Ragusa follows up.

This Nate Silver forecast post for Iowa is a good read for thinking about how to forecast, although a bit out of date in those fast-changin’ Hawkeye polls.

Ta-Nehisi Coates shoots down all your fantasies about how you would behave if you were a slave or a poor black kid. He then reacts to some Megan McCardle comments here.

Andrew Sullivan gives his GOP primary endorsement to Ron Paul. It’s kind of a left-handed endorsement but — hey — I’m left-handed and I agree with more of it than I don’t!

Meanwhile, some idiots are arguing that being left-handed doesn’t make you smarter. yeah, right.

Jon Bernstein on why there ain’t gonna be a new candidate in the GOP race. And here with a great reminder of why democracy isn’t perfect, but it’s still the best.

What does Santa’s workload profile look like?

Matt Yglesias had a couple of nice posts (here and here) on online piracy. And he models a Skyrim shock to the economy here.

Ezra Klein offers some preliminary thoughts on the Ryan-Wyden Medicare plan. A wider roundup from Sullivan here. I expect we’ll be hearing a ton about this in the coming weeks.

Glenn Greenwald is as depressed as I am that Obama is going to sign the NDAA that includes indefinite detention. Balko mocks POTUS and Congress for their behavior on Bill of Rights Day.

How drunk can you get at your office Christmas party?

Stephen Griffin is starting a series of posts about war powers, based on his forthcoming book.

Randy Bachman describes how the first chord of A Hard Day’s Night is actually played.

Josh Krashaar wrote today about the possibility of a tied electoral college, 269 to 269, which would hand the election to the House of Representatives, since neither candidate would have a majority.

Way back in October 2004, I wrote a piece which raises a little-known fact about such House-thrown elections: the 12th amendment puts the top three electoral vote recipients on the ballot in the House. This was obviously intended to manage the (then) more likely scenario of no one getting a majority because three or more candidates won votes, but it would hold true in a tie scenario. Which means that electors in the electoral college — particularly those aligned with the party that did not control the most state delegations — would have incentives to strategically vote not for their assigned candidate, but for a third candidate, to create a three way race. This could create wonderfully crazy situations.

Anyway, the full article appears below. Enjoy.

———————-

Interested in becoming president this year? If so, hope for an electoral college tie. With an unlikely, but plausible, perfect tie — 269 electoral votes for both George W. Bush and John Kerry — anyone meeting the Constitutional qualifications could end up president. Here’s how.

Most people know the electoral college, and not popular vote, decides presidential elections. Many people also know that if no one gets a majority of electoral college votes the Constitution directs the House of Representatives to choose the President. This has happened twice (not counting 1876, a technically different situation) — in the strange tie of 1800 and the 4-way election of 1824. The contemporary prospects for a House election are slim. Only an electoral tie — or the longshot possibility of a third party winning electors — can produce it. However, a tie is plausible this year: if all states vote the same as 2000 except New Hampshire and Nevada, the electoral vote would be 269 to 269.

An electoral college tie would produce overwhelming media attention on the possibility of “faithless electors“, who disregard the vote return in his/her state and pick whichever candidate he/she wishes. In 2000, such a move by three electors would have produced a Gore victory. Earlier this month, a Republican elector, Richie Rob, made rumblings that he might not elect Bush if the President wins West Virginia.

A more intriguing, and potentially more consequential, possibility is an elector “shedding” a vote to a 3rd candidate. In an election thrown to the House, the 12th amendment specifies to choose from the top three electoral vote recipients. In a tie, only Bush and Kerry will have electoral votes, unless some elector decides to shed his vote, making the outcome 269-268-1. Why would an elector do this?

It’s simple. Shedding a vote would still send the election to the House. And currently, the Republicans would handily win a vote between Bush and Kerry. Democratic electors thus have an incentive to get a third candidate on the House ballot — particularly a centrist who could draw moderate Republicans into a coalition with the House Democrats to defeat Bush. To succeed, it would have to be a prominent moderate Republican, and it would have to be someone willing to attempt a revolt in the Republican party. It would almost have to be John McCain.

While McCain might reject this and throw his support behind Bush, he also might seize the opportunity, much like Aaron Burr did in 1800. It would be his chance to reshape the GOP. He has never personally liked Bush. And lest we forget, it could make him president. Certainly there are House GOP members who would prefer a moderate Republican like McCain over Bush.

Bush Republicans would obviously try to prevent such a revolt. McCain, however, would not need many GOP defectors to make it work. The 12th amendment happens to also specify that the House vote is by state delegations, not simple majority. To win, you must get the vote of 26 state delegations. Along strict partisan lines, there are currently 30 GOP delegations, 16 Democratic delegations (including Vermont’s independent but left leaning Bernie Sanders), and 4 deadlocked delegations.

Imagine a three-way House choice between Bush, Kerry, and McCain. McCain could prevent Bush from gaining the required 26 states by deadlocking 5 states. Assuming full Democratic support for McCain, defection of less than a dozen key GOP members could deny Bush victory. After a first ballot impasse, it’s anybody’s game, but McCain, as the moderate of the three, would be a strong contender to win a politically brokered deal.

But Bush Republicans might act even earlier. Think back to the original “shedding” of an elector to McCain. Although a tie vote would be known immediately after the election in early November, the electors do not meet to cast votes until December, giving them time to consider their options. The obvious Bush Republican counter-attack would be to encourage multiple Republican electors to shed votes. Multiple electors shed toward either a left-winger (say, Howard Dean) or a right-winger (say, Tom DeLay), could keep a moderate, agreeable third candidate such as McCain out of the contest, making the House vote between Bush, Kerry, and a radical. The House GOP would hold together, and Bush would win handily.

But why would the Democratic electors allow this? They could plan to shed more electors towards McCain. A race to the bottom could then ensue, such that any radical combination of electoral votes, even scenarios where Bush or Kerry get few or no votes, could occur. Depending on what degree electors are aware of the possibilities and to what degree they coordinate their actions, almost any three candidate could end up in the House.

While farfetched, the idea of the perfect electoral tie and electoral shedding opens the frightening possibility of an American election in true disarray — one in which anyone, announced candidate or not, could end up President. Even you.

Last night, it became clear that the omnibus appropriations bill might not make it out of conference, apparently due to political issues related to to the payroll tax cut extension. In order to prepare for this possibility, late in the evening on Wednesday, three new pieces of legislation — including a new omnibus — were introduced in the House. At 11:40pm, the House adjourned. At 12:37am, the House Rules Committee added the three newly-introduced pieces of legislation to its website calendar of expected activity for the week, but took no official action on them.

With the possibility of a government shutdown looming on Friday night, several observers, cognizant of the chamber rules, remarked on the speed at which the House would be able to take up the new bills if the conference report did indeed fall apart. Here’s CQ ($):

Despite late-night hurried efforts, they missed the Wednesday filing deadline by about a half hour, making it unclear when the House will vote on the package. The chamber’s rules require that a full calendar day intervene between the publication of a bill text and a vote, but the current stopgap continuing resolution that funds most of the federal government (PL 112-55) expires Friday.

I’m not trying to pick on CQ — a lot of people said similar things — but while that paragraph gets the gist of things, it’s not really even close to correct. First off, the continuing resolution funds the government through Friday, so a funding gap can be averted with action taken anytime prior to Friday evening at midnight, me. Second, while there are definitely chamber rules that require bills to be available for a period of time prior to action, it’s (1) not a one-day intervening provision, (2) not a “calendar day” issue, and (3) not a gap between the publication of text and a vote.

Ok. There’s just a ton to talk about here. Let’s do it Q&A style.

Q: Bottom line: how quickly can you can get a brand-new bill you just wrote onto the House floor for consideration?

A: The most straightforward answer is this: assuming you want to structure the consideration of the bill and you don’t have a 2/3 supermajority supporting you, then you need to let at least one special rule lie over for one legislative day. That can technically be accomplished in just a few minutes, but in usual practice it means that if you generate something today, you can’t consider it until tomorrow.

Q: What the hell did you just say?

A: Ok. Let’s start from the beginning…

Q: How do you get something onto the floor of the House?

A: In order to be brought up on the floor, a measure usually has to be “privileged.” Under the normal chamber rules, only certain measures are privileged for floor consideration as certain times. In practice, there are two methods commonly used to achieve this privilege for something that is otherwise not privileged at the moment. The first is to suspend the rules. But that requires a 2/3 majority, and thus is usually only available for non-controversial legislation. The other method is for the House to adopt a special rule that grants privilege to your measure.

Q: But how do you get the special rule onto the floor?

A: Special Rules are House Resolutions reported from the Rules Committee. Under the general chamber Rules, such resolutions are automatically privileged. And so the Rules Committee — which is closely aligned with the leadership in the modern House — has the gate-keeping power to determine what measured will be made privileged for consideration.

Q: So the Rules Committee decides what comes to the floor?

A: Not exactly. Ultimately, the full membership of the chamber is in control of the rules. Change to the rules — no matter how temporary or minimal — must be approved by the chamber. Therefore, resolutions from the Rules Committee proposing special rules are adopted by the House by majority vote. In practice, the majority party virtually always holds together to support the rule. In some Congressses, not a single rule fails on the floor. When a rule is taken down on the floor, it’s a pretty clear sign that there is a major disagreement in the majority party.

Q: So why can’t they just write a special rule, immediately pass it on the floor, and then take up the newly privileged bill?

A: Because the chamber rules prohibit consideration of a special rule on the same legislative day it was reported from the Rules Committee. All special rules must lie over one legislative day. There are three exceptions to this: first, if it’s the last three days of a session; second, the one-day layover can be waived by a 2/3 vote on the floor; and third, it doesn’t apply if the special rule’s only purpose is to waive the three-day availability requirement for committee reports and conference reports.

Q: Wait, there’s a 3-day availability requirement?

A: Yes. Under chamber rules, measures reported by committee (and conference reports reported by conference committees) may not be considered on the floor until the text of the committee/conference report has been available for three calendar days. Similarly, unreported bills and resolutions may not be considered on the floor unless the text has been available for three calendar days.

Q: So how can they possibly consider the new omnibus prior to the Friday night deadline?

A: A special rule can be written that waives the three-day requirement.

Q: So special rules can just waive any rule of the House?

A: More or less. The only exceptions are that a special rule cannot waive the minority’s right to offer a motion to recommit a bill, and cannot waive the point of order against an unfunded mandate. But remember, a majority of the House has to agree to a special rule.

Q: So are these waivers common?

A: Yes, very much so. Virtually all controversial legislation moves through the House under a special rule. And most of those special rules waive all possible points of order against the bill: timing limitations such as the 3-day availability, content limitations such as the restriction on authorization legislation in appropriations bills, and amendment limitations, most importantly the restriction that amendments be germane. It’s the main reason that the majority doesn’t really have to sweat all of these requirements — they can all be waived by special rule.

Q: Wait, so the special rule also structures the amendment process for the bill?

A: Yup. At least most of the time. This is perhaps the chief substantive function of the rule. A rule might be “open” — allowing any and all germane amendments — but in the modern practice, rules are much more likely to be “closed” (no amendments allowed) or “structured” (allowing only certain amendments pre-approved by the rule.)

Q: How do you get an amendment into the rule?

A: When the Rules Committee is considering a special rule, Members may submit proposed amendments to the underlying bill, and then come and testify at the Rules Committee hearing on the special rule. The Rules Committee then decides which amendments to the bill to allow into the rule.

Q: So what does a rule look like?

A: As an example, here’s the complete text of H.Res.54, which provided for the consideration of H.359:

Resolved, That at any time after the adoption of this resolution the Speaker may, pursuant to clause 2(b) of rule XVIII, declare the House resolved into the Committee of the Whole House on the state of the Union for consideration of the bill (H.R. 359) to reduce Federal spending and the deficit by terminating taxpayer financing of presidential election campaigns and party conventions. The first reading of the bill shall be dispensed with. All points of order against consideration of the bill are waived. General debate shall be confined to the bill and shall not exceed one hour equally divided among and controlled by the chair and ranking minority member of the Committee on Ways and Means and the chair and ranking minority member of the Committee on House Administration. After general debate the bill shall be considered for amendment under the five-minute rule for a period not to exceed five hours. The bill shall be considered as read. All points of order against provisions in the bill are waived. No amendment to the bill shall be in order except those printed in the portion of the Congressional Record designated for that purpose in clause 8 of rule XVIII and except pro forma amendments for the purpose of debate. Each amendment so printed may be offered only by the Member who caused it to be printed or a designee and shall be considered as read. At the conclusion of consideration of the bill for amendment the Committee shall rise and report the bill to the House with such amendments as may have been adopted. The previous question shall be considered as ordered on the bill and amendments thereto to final passage without intervening motion except one motion to recommit with or without instructions.

Note that the rule (1) provides for H.359 to be brought up on the floor; (2) structures debate; (3) waives all points of order against the bill; (4) makes in order any amendment that was pre-printed in the Congressional Record; (5) provides for five hours of total time for amending; and (6) makes provisions for a final passage vote to occur. A special rule is almost always accompanied by a short report explaining its provisions and listing votes taken in the committee; you can read the report for H.Res.54 here.

Q: So all of this supersedes the chamber rules?

A: Yes, assuming the special rule was validly adopted by the House. Much like a unanimous consent order in the Senate, the special rule governs proceedings as if it was the chamber rules for the duration for which it is in force.

Q: So what rules structure the debate on the special rule?

A: The chamber rules. Privileged resolutions from the Rules Committee are debated under the Hour rule in the House. That means that the Member that calls up the special rule (usually the chair of the Rules committee is the floor manager for a special rule) is given one hour for debate, half of which is customarily yielded to the minority. After that hour of debate, the floor manager moves the previous question, and assuming that it is ordered by the House, the rule is then voted upon.

Q: Back to the new omnibus bill. Walk through the whole thing again.

A: The Rules Committee will draft a rule, and perhaps hold a hearing on it for amendments. They will report the rule, and then on the next legislative day, the rule will be privileged for consideration. The House will consider the rule, which will waive the three-day availability requirement for the new omnibus bill and structure the debate and amendment process for the bill. The House will then vote on the rule, and if it passes the bill will be privileged for consideration and can be brought up immediately.

Q: So if they report the special rule out of committee today, this can happen tomorrow?

A: In all likelihood, yes. But that’s not necessarily the case. Chamber rules require that special rules from the Rules Committee lie over for one legislative day, which is different than a calendar day. A new legislative day begins when the House meets after an adjournment, and ends when the House adjourns. Usually, this lines up with the calendar day — the House adjourns sometime in the evening, and then meets again the next morning.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. The House could choose to adjourn in the middle of the afternoon for just a matter of minutes, and then upon return from the adjournment a new legislative day would have begun. Likewise, the House could recess overnight, and when the recess ended the next calendar day, a new legislative day would not have been created.

Q: So why doesn’t the majority just always adjourn for two minutes as a strategy?

A: There’s a pretty strong norm against it. The one-day layover rule exists so that you can’t surprise people with stuff on the floor. And that’s a sensible rule for a professionalized legislature. To allow the majority to instantly bring up anything at any time is potentially problematic. So using strategic adjournments is generally frowned-upon. It would definitely fall into the category of hardball.

Q: So what’s the significance of midnight in regard to the special rule?

A: Technically, nothing. Take last night, for example. The House adjourned at 11:40pm. At that point, even if the Rules Committee completed work on a special rule prior to midnight, it would not qualify to be reported to the floor on the legislative day that had been created on Wednesday morning. Conversely, if the House had not adjourned, then the Rules Committee could have taken as long as it wanted to report out a special rule, even if it happened after midnight. This happens upon occasion — the House is kept in session very late into the night in order to allow the Rules Committee to report a special rule out. After that, the House adjourns, and even if the adjournment was at 5am and the House meets again at 9am, the special rule will have laid over the requisite one legislative day.

Q: Are there other ways of bypassing the one-day layover rule for special rules?

A: Yes. The most common is to write a special rule changing that rule — waiving the special rule layover rule!

Q: Why would you do that? Wouldn’t that special rule need to lie for one day?

A: Yes, it would. But consider the following circumstance: you know you want to do something tomorrow, but you don’t have the bill ready to be introduced. So what you do is write a special rule today that, in effect, says “special rules do not have to lie over one day, but can be considered immediately.” Then, the next day you can pass that rule, and then you can immediately bring the real rule to the floor, pass that, and then you can bring the bill to the floor.

Q: Does that really happen?

A:Yes, with some regularity. It happened back on July 29, when H.Res.382 was passed. Here’s the full text:

Resolved, That the requirement of clause 6(a) of rule XIII for a two-thirds vote to consider a report from the Committee on Rules on the same day it is presented to the House is waived with respect to any resolution reported through the legislative day of August 2, 2011.

Note that it simply waivers the 2/3 requirement, since (as mentioned above) any privileged resolution from the Rules Committee can be adopted same-day if it gets 2/3 vote. The rule was passed during the debt ceiling negotiations, so that if things came down to the wire on August 2, a rule and a bill could be moved quickly.

Q: You mentioned that the layover rule and the availability rules don’t apply at the end of the session.

A: That’s right. The current chamber rules waive the one-day layover for special rules during the last three days of a session and waive the availability rule for bills and conference reports during the last six days of session. Since the House often does not pass an end-of-session adjournment resolution until right before it happens, those last days are often unknowns. To combat this, the House will occasionally pass a special rule toward the end of a session waiving the one-day layover or the three-day availability for the remainder of the session.

Q: All of this sounds nothing like the Senate.

A: That’s right, because it’s not anything like the Senate. The Senate can really only adopt the equivalent of a special rule by unanimous consent, and that is one of the key functional differences between the chambers: the majority in the House can more of less do what it wants, because it can change the rules at will. The minority protections in the Senate prevent changes to the rules by a simple majority, and therefore things like structuring debate or limiting amendment can only be accomplished by unanimous consent or complicated strategic maneuvering.

Matt Yglesias is backing a proposal by Senator Lieberman that would allow any legislation that meets the supercommittee charged standard (i.e. achieves $1.5 trillion in additional deficit reduction over 10 years, has bipartisan support) to receive the expedited consideration that was arranged for the supercommittee legislation (i.e. no filibusters, no amendments). The idea is to allow a thousand supercommittees to bloom. Here’s Lieberman (via Brian Buetler):

The Budget Control Act said that if the Super Committee reached an agreement it would come to congress and for good reasons it would be considered on an expedited basis, it would not be subject to a filibuster, it wouldn’t even be subject to amendments — it would be an up or down vote,” Lieberman told reporters at a breakfast round table hosted by the Christian Science Monitor. “The proposal I’m introducing today would extend that process for 90 days into next year…but I’ve done it a little differently since the Super Committee is gone. I’ve said that if any six members of one caucus, six members of the other caucus in the Senate; [or] 15 in the [both caucuses] in the House…submit legislation that is qualified under the bill, which means that it would achieve at least $1.5 trillion of additional debt reduction over the next 10 years, and of course it’s bipartisan, then it would have the benefit of those expedited procedures.

I suppose the goal of Lieberman’s proposal is to have some “gang of 12” produce a moderate bill that would capture significant votes from both parties in an up/down vote but that might lose votes from both wings. That, I suppose, could potentially be effective if those wings would have blocked a cloture vote on the same bill. I don’t think it’s necessarily a bad idea on its face. The problem, as I see is, is that the bipartisan support requirement of 6 Senators from each caucus results in a potential asymmetry for the ramming through of partisan bills.

If you make the (not unreasonable) assumptions that all Democrats are more liberal than any Republican (and vice-versa), then the upshot of Lieberman’s proposal is that any Democratic ideas for deficit reduction will require 59 votes in the Senate (53 Democrats plus 6 Republicans) while GOP ideas for deficit reduction require only 53 votes (47 Republicans plus 6 Democrats). In effect, you are asking both parties, “Can you pick off 6 votes from the other side?” It’s just that when the Democrats pick off six votes, they are almost at the cloture threshold. When the GOP does it, they barely have a majority. That strikes me as a large concession on the part of the liberals.

Now, each side also has a backstop — the House for the GOP, the President for the Democrats — and I don’t think the proposal is going anywhere, so I don’t want to make too much of it. But having any six Senators from each side support a bill is very different than having the supercommittee — which was chosen by the leadership — support a bill. And while I think it would be possible under the Lieberman plan for a moderate bipartisan bill to get through the Senate, I think it is much more likely that the result would be a (GOP + conservative Dems) bill that got the votes to pass.

And so it should not be all that surprising that the legislation (S. 1985) currently has four co-sponsors — Senators Corker, Enzi, Kirk, and Murkowski — and all of them are Republicans.

In the wake of the Senate’s failure to invoke cloture on the nominations of Caitlin Halligan to the D.C. Court of Appeals and Richard Cordray to head the new Consumer Protection Board, there has been a lot of criticism about the filibuster. A number of writers are very concerned about the use of the filibuster to deny confirmation to an agency head as a protest against the agency itself. Steven Benen called it “extortion politics.” Jonathan Cohn likens it to antebellum nullification, echoing Tom Mann’s assessment from this past summer. I’m not sure I agree with the use of the term “nullification,” but I see where they are coming from. It’s definitely an institutional development.

Personally, I like the more neutral and wider formulation that Jon Bernstein uses (via Mark Tushnet): hardball (see here and here and here). The idea of hardball is pretty straightforward: an institution like the Senate is governed by rules and standing orders and precedents, but it is also governed by norms. When political actors abandon the norms and insist (as they have every right) on the literal enforcement of the rules, short-term strategic advantage (for an individual or party) can often be gained. A popular example of such a norm was the past practice of not filibustering judicial nominations purely on partisan or ideological grounds. But it can be applied across any set of norms, and is by no means limited to the Senate, or even politics for that matter.

There’s nothing extra-legal or inherently wrong with hardball. Quite to the contrary, it’s every Senators right to take full advantage of the rules and demand that they be followed. The problem, however, is that the short-term advantages an individual or faction can derive from hardball often create undesirable situations when universalized. As more and more individuals (or both parties) abandon a given norm in favor of the strict rules, the comparative advantage recedes and the resulting equilibrium may create an institutional context that nobody prefers to the old system of norms. Multiply this across a whole range of different norms, and you have a potentially serious problem.

A good analogy is college basketball. By the early 80’s, two norms had completely broken down in favor of the strict rules: late-game fouling to stop the clock to put the other team on the line for a 1-and-1, and stalling with the ball when holding a lead late in the game. Both of these strategies are wise, but when universalized and maximized they began to destroy college basketball, especially when set together in concert: teams with leads began stalling earlier and earlier (sometimes with 5 or more minutes to go in the second half), and in response teams that were losing began fouling earlier and earlier.

The final minutes of college basketball games were no longer resembling basketball games at all. Even worse, inferior teams began to realize that they could build their entire strategy around these concepts. Hold the ball for minutes at a time to reduce the number of possessions (and therefore increase the variance/luck of the outcome), and intentionally foul to produce 1-and-1’s. The solution, luckily, was relatively simple: change the rules. A 45-second shot clock was introduced for the ’85-86 season, and later the “double bonus” was added so that continuous fouling would result in 2 shots, not 1-and-1. It hasn’t completely solved things (and never will) — teams still have incentive to foul and incentive to use up the shot clock — but it has severely reduced the problem.

As you might have guessed, though, it’s not exactly easy to change the rules in the Senate.

All of this is context swirling around the main point I want to make here, which is that while hardball may be on the rise in the Senate, we’re nowhere near anyone playing absolute hardball with the Senate rules. The system is still largely held together by norms. Think about the defeat of the motions to invoke cloture on Halligan and Cordray. Both of those cloture votes were scheduled by unanimous consent. In fact, just check out the order passed by unanimous consent last Wednesday night:

I ask unanimous consent that when the Senate completes its business today, it adjourn until 9:30 a.m., on Thursday, December 8, 2011; that following the prayer and pledge, the Journal of proceedings be approved to date, the morning hour be deemed expired, and the time for the two leaders be reserved for their use later in the day; that following any leader remarks, the Senate proceed to executive session to consider Calendar No. 413, the nomination of Richard Cordray to be Director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, with the time until 10:30 a.m. equally divided and controlled between the two leaders or their designees; and that the cloture vote on the Cordray nomination occur at 10:30 a.m.; finally, that if cloture is not invoked, the Senate resume legislative session and resume consideration of the motion to proceed to S. 1944.

There’s a UC in there for (1) adjournment, (2) approval of the journal, (3) the expiration of morning hour, (4) proceeding to executive session, (5) debate structure and limits on the nomination prior to the cloture vote, (6) the timing of the cloture vote, and (7) the return to legislative session if the cloture vote fails. That’s a window into just how much is done in the Senate by unanimous consent. And remember, that’s just one UC agreement. There are dozens of things that are routinely dispensed with by UC: the first and second reading of bills, the reading of amendments, the live quorum calls prior to cloture votes, the ending of strategic quorum calls, and so on. And this isn’t unusual: the Senate floor is more or less run by unanimous consent. Every day. Even when it’s being locked up by a filibuster.

And therefore, if any individual Senator wanted to really gum up the works on any given day, it’s certainly not hard. You can just go down to the floor and sit at your desk and object to everything. Floor time is already scarce, and having to read the journal and hold morning hour and read all bills and all amendments and hold a live quorum call prior to all cloture votes would only make it more so. There are incredible stories of Howard Metzenbaum doing just this a generation ago: sitting at his desk in the Senate and objecting to every single UC until whatever concern he had was mollified. Now that’s hardball. Now again, the point here is not that people aren’t playing hardball with nominations, they are. The point is that there’s a lot of hardball left to be played before the norms completely break down. Which, of course, raises a key question: why don’t Senators play absolute hardball?

There are a few reasons. First, individual Senators need help in accomplishing their own goals. The norms aren’t simply held in place by tradition; there are strong ambition incentives that bind people to them. The Senate is a repeated game, and while absolute hardball may get you a short-term victory, it’s likely to be a long-term disaster. While Senate leaders and the party caucuses aren’t all-powerful, they do control enough goodies and have enough discretion that they can harness the ambitions of individual Senators to keep them in line. A Senator with no long term goals and an interest in jamming up the floor would be dangerous indeed. But luckily for the Senate, most Senators have policy and/or political goals of their own that they would like the advance. And so looming over any individual who is considering all-out hardball is the threat of losing all support for their own current and future goals. And thus the lack of rouge lone wolf ultra-objectors.

Second, individuals and minority parties need to worry about the majority changing the rules. If you locked down the Senate floor by announcing that you were going to object to every single unanimous consent request from here on forward, my guess is that the rules would change rather quickly in some way (perhaps as simply as by putting in a new rule that allowed “unanimous consent” unless two objections were heard!). Or they’d just expel you. But this is a key point: Senators and parties playing hardball in the modern age aren’t upset by the current system; they see the current system as benefiting them. They aren’t out to change the rules, they’re simply out to exploit the rules to maximum benefit. And therefore they need to walk a tightrope line. Yes, the minority could demand all post-cloture rights and use up the 30 hours of debate and never agree to schedule a cloture vote by UC and just demand “regular order” at all times. But it would ultimately backfire.

On the other hand, thinking about the future, the Senator or group of Senators who might want to play absolute hardball are the person or persons who want to radically amend the current system of rules. That person/persons will not live in fear of the rules being changed, but instead will welcome it. Some future group of Senators, perhaps only a handful, will take to the floor, Metzenbaum-style, and simply object to everything until they are mollified. But unlike Metzenbaum, they will not be seeking leverage over public policy; they will be seeking to change the rules themselves. And if they can prove that they don’t care about being punished by the leadership or marginalized by the rest of the chamber, they will succeed. Because the Senate will only have three choices: sit in complete gridlock; change the rules to mollify the objectors; or change the rules to get around the objectors. The first is not tenable, and the latter two achieve the same end for the hardballers.

There’s a strange sort of symmetry to all of this: the setting aside of norms in favor of hardball is both the cause of much consternation about the Senate, but also a potential solution to it. Those upset by the exploitation of the rules may come to see the exploitation of the rules as the way out of the hardball spiral. I have no crystal ball into the future of the Senate, nor do I think we are particularly close to the snapping point over the norms/rules. But the steam seems to be building a bit, and the release valves that currently exist — most importantly landslide elections — may not be enough to thwart a growing sense among some that the rules need to change, and that absolute hardball is the way to change them.

Mitt Romney, from Saturday night’s GOP primary debate:

We don’t need– we don’t need folks who are lifetime– lifetime Washington people to– to– to get this country out of the mess it’s in. We need people from outside Washington.

You hear this a lot, the idea that coming in as an outsider to shake up the Washington establishment is a good way to advance policy goals or solve political problems. Whatever the merits of it — and it’s pretty clear that there are advantages to be an insider and advantages to being an outsider, but not obvious that the latter outweigh the former — I think it tends to obscure a pretty basic institutional reality in DC: the President, regardless of whether he’s spent his life in the Senate or his life farming in rural Montana, is functionally an outsider during the time he is President.

Now, of course the President can be a DC insider in the sense that he/she could have spent a long career in the Senate, have political and bureaucratic connections all over town, know all the lobbyist and journalists, and be a master of the Washington political game. Sure. What I mean is that the presidency itself creates an institutional situation in which President has fully unique goals and strategies, and that those goals and strategies are not only different than what observers typically would describe as the goals and strategies of “lifetime Washington people,” but in most respects are actually in conflict with them. There’s a lot that could be said about this, but two important aspects are (1) the President has a completely different time horizon than most of the rest of Washington; and (2) the President’s needs to win in ways that Members of Congress do not.

The time horizon is obvious, but sometimes under-appreciated. Presidents have at most eight years to accomplish any objectives, while Members of Congress, senior executive branch officials, and private sector DC political actors may very well expect to be around for decades. Consequently, the president almost always seems more in a hurry than Congress to Get Big Things Done. And from this, of course, flows one of the basic political differences between Members and Presidents: Members are often more naturally risk-averse. The micro-result is that presidents tend to be frustrated by the long and slow congressional policy-making process, and the macro-result is that DC often appears to be in the situation in which a President is prodding a recalcitrant Congress to take up his policy proposals.

There’s more to it than that, though. In the long run, the basic bargaining outlook for the President and a Member of Congress differ. The President’s short and known time horizon suggests that he should accumulate as much political capital as he can, but also that he should leave office with the tank on empty: if he can put to work every last chit and favor and piece of patronage he has in order to call in every last vote or favor he needs, that’s a solid utility maximizing strategy. Similarly, he doesn’t have to worry too much about burning bridges, especially as time goes on. In other words, the short time horizon not only incentivizes the President to work quickly, but it also suggests a slash-and-burn strategy, at least in comparison with Members or bureaucrats, whose long-term incentives suggest maintaining capital, using it shrewdly, and avoiding the creation of permanent enemies.

The second aspect I brought up — that the President needs to win in ways Members do not — is something that often drives people batty when they watch C-SPAN. It’s not at all uncommon to see a contentious vote taking place on the floor of the House or Senate, and for the Members to be having friendly, casual conversations with one another, even if they voting on opposite sides of the issue. Beyond the basic civility of a legislature and the need for maintaining long-term friendships, there’s a good institutional reason for this: Members of Congress do not have to win in order to keep their jobs; they simply have to vote the right way. As David Mayhew put it in The Electoral Connection, if Members of Congress had to win on the floor in order to get re-elected, they would tear each other to shreds. But they don’t: in the typical situation, the job of a Member is to well-represent his constituents, and since no individual Member can control the outcome in Congress, voters (quite sensibly) mostly take into account how a Member votes, not if the Member’s side of the vote carried the day.

This is mostly not true for the President. While position-taking is of some use to a President (especially in situations of divided government), results are far more important. For a President to go to the voters and say that he stood for the right things is a weak argument indeed. And the consequence of this is often revealed, once again, in the political temperament of the President. No one in Congress likes to lose, but no President can really afford to lose. And so while all Presidents strive to be good Neustadtian bargainers, most also cannot resist the temptation to lash out on occasion, and to take risky actions in the hopes of delivering victories.

When you combine the need to win with the short time horizon, the sum total is an institutional actor who is quite seriously incongruous with the other political actors in and around the government. As Neustadt wrote, no one else sees what the President sees. And so it’s not surprising that Presidents tend to create bunker-like mentalities within the EOP and especially the White House staff. Nor should we be surprised that that the White House often has rocky relations with its own congressional party. Or that the President finds Washington or the pace of congressional action too slow or the tactics of the existing DC political establishment too risk-averse.

The President may be the center of political power in Washington, but as an institutional actor in the federal government, he’s mostly a lonely outsider.

From the transcript of Saturday night’s GOP debate:

DIANE SAWYER: That is true. And it’s 24 days now and counting until the voting begins in the caucuses. And– and it’s at the time for closing arguments, so let us introduce the presidential candidates from the Republican party for the United States of America here at the debate tonight.

Former Senator Rick Santorum of Pennsylvania, Governor Rick Perry of Texas, former Governor Mitt Romney of Massachusetts (AUDIENCE WHOOP), former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich of Georgia (AUDIENCE WHOOP), Texas Congressman Ron Paul, (APPLAUSE) and Congresswoman from Minnesota, Michele Bachmann. (APPLAUSE) Thank you all.

I think it’s pretty obvious that the “whoop” factor has been underestimated as an explanatory variable for primary success thus far this cycle.

David Post’s guide for students on exam-taking mistakes.

Newt Gingrich is a populist technocrat, says Conor Friedersdorf. And then he demolishes him here. Lots of people are saying Gingrich can or can’t win the nomination. Call me a beltway insider, but I say “no chance.” And I basically agree with Ezra’s reasoning here.

President Obama gave a speech this week. He paralleled his presidency and outlook to Teddy Roosevelt. I thought Jonathan Chait’s roundup and critique was interesting.

A libertarian reminder that entrenched corporate power is partially a product of the left.

Matt Yglesias on why you should give money, not canned goods, to food charities.

Freeman Dyson’s review of Daniel Kahneman’s new book “Thinking, Fast and Slow” is excellent.

Greg Koger wonders why the President doesn’t use the pardon power to greater ends. Suzy Khimm provides an answer.

John sides on demographics and being careful with the independent vote.

Nate Silver on why Cain fell.

Ryan Avent looking through the Economist in 1931.

There’s a bunch of talk about brokered conventions. Rhodes Cook says possible. Josh Putnam thinks not. Nate Sliver sees it as possible. Jon Bernstein is dismissive at first, and then thoroughly convincing later.

Senate nominations are losing cloture votes. RIP, Gang of 14 says Bernstein, and advises recess appointments. Jonathan Cohn calls it nullification.

The baby boomers control Christmas.

I liked this article on how doctors die.

Just about the best example you’ll find of a professional class extracting unnecessary licensing from the government in order to stifle competition.

It takes a village to make a cheeseburger.

Paul Krugman trys to minimize Hayek’s economic contributions. A stiff response here.

A lot of people forwarded me that “Gingrich broke the law by saying hed appoint Bolton” link. Evidently, it’s not true.

I’m a sucker for posts about Animal Farm. See also here.

Tyler Cowen piece on the effects of the Moneyball revolution.

Ta-Nehisi Coates interviews Eric Foner about the civil war. And wraps up the “Is the Civil War Tragic?” debate here.

The science of temper tantrums.

What do we do when the legislature wants more presidential power than the president does? Good question.

Thinking about how #OWS will affect the Democratic Convention next year, and comparing it to Chicago ’68. I also liked this #OWS commentary by Will Wilkinson.

A nice visual illustration of the correlation/causation distinction.