People keep pointing me toward E.J. Dionne’s op-ed in today’s Post. I’m not all that enthused about it, in part because the analogy is absurdly tortured and the history is a bit stylized, but mostly because I don’t see how the lesson of Lincoln can be applied here. Let me explain.

People keep pointing me toward E.J. Dionne’s op-ed in today’s Post. I’m not all that enthused about it, in part because the analogy is absurdly tortured and the history is a bit stylized, but mostly because I don’t see how the lesson of Lincoln can be applied here. Let me explain.

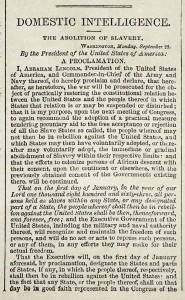

Dionne’s pitch is pretty simple: Lincoln was a moderate anti-slavery man, who ran in 1860 with a conciliatory attitude toward the south, and continued that policy not only during the secession crisis, but also after the war began. He carefully worked to hold the center, ever fearful that if perceived as an abolitionist, both he and the cause would be sunk. The conciliation, however, got him nowhere. Meanwhile, public opinion in the north was drifting toward the abolitionists, who believed that ending slavery was the only way to solidify the section and win the war. Lincoln then seized the opportunity by abandoning his centrist position and issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, a year and a half into the war.

Dionne then transfers this analogy to present-day. Obama is situated similarly to Lincoln, facing a hardened opposition that refuses to respond to his centrist overtures, and a growing leftist movement is making inroads with public opinion. As Dionne says, “[b]y following Lincoln’s example and acting against the injustices of our time, Obama could also come to occupy the high ground.”

But here’s the problem: what do you do? Even if you fully accept Dionne’s reading of history — and while I would quibble with a lot of it, it’s certainly not unreasonable — you still have to face up to the biggest shortcoming of the analogy: there’s no equivalent of the Emancipation Proclamation available to president Obama. Part of the simplicity of Lincoln’s situation is that he was able to act in a way that was both decisive and unilateral. The total sum of the injustice of slavery was not 100% rectified by freeing the slaves, but it was about as complete of a solution as anyone could possibly demand. No one who agreed with the ends was suggesting alternative means, or worried that Lincoln’s means would not achieve the ends. And Lincoln was able to execute the policy via nothing more than an executive order and an expansive-but-perfectly-plausible reading of Article II of the Constitution.

I would respectfully suggest that Obama has no such recourse. It’s telling that Dionne does not make specific suggestions for what the president should do; it’s pretty hard to think of concrete policy actions he can unilaterally take regarding economic inequality and perceived excesses of the financial sector. If we were to reverse the analogy, it would be like demanding Lincoln free the slaves, but require him to do it by legislation and with the southerners allowed to vote. Yes, Occupy Wall Street may be genuinely moving public opinion. But it doesn’t just have to get center-left Democrats like Obama (i.e. the median northern voter in 1862) to take up more aggressively liberal positions, it needs to move at least some right-of-center voters to those positions (i.e. the median national voter in 1860). Obama’s main opposition, unlike Lincoln’s, has yet to exit the democratic process.

More to the point, the one specific that Dionne mentions — higher taxes for the wealthy — has been proposed by Obama time and again since the 2008 election. And in the context of the current debate on the left, it’s small beer. Raising taxes on the runaway wealthy— while certainly noble — is not going to fix the economy, close the deficit, or significantly lower unemployment. And even if that is the sum total of policy necessary to grab the high ground in the face of the abolitionist-like angst, you still have the southerners to deal with. One highly likely outcome is that you are left with a campaign issue and not a policy. Ditto on the jobs package. Ditto on another stimulus. Ditto on pretty much everything.

But, I can hear you thinking, maybe that’s what Dionne is saying! Obama should move his stated preferences to the left and capture the moral high ground in preparation for the 2012 election. In that case, Dionne has not exactly written a new column. And while I know a lot of people think that’s a good strategy, I think it’s dubious. The president has already reshaped some of his policy ideas to conform to an election narrative of GOP obstructionism. If he moves them further left in a way that makes it plain that he’s not interested in policy outcomes right now, the voters are unlikely to cancel out the blame for gridlock. Much more likely is that the President will lose.

Lincoln was a smart politician, who understood his political context and how to modify his policies within it. I’m not convinced his move would be to lurch left right now. And I don’t think Obama’s will be either.