Yesterday, in making a point about the filibuster, I mentioned that one fundamental difference between the House and Senate is the relative ease by which the partisan House majority can block minority amendments, even if those amendments have the support of the (numerical) majority of the chamber. As I’ve written about before, this has pretty big consequences for the deliberative nature of the chambers:

If deliberation is to mean anything in legislative politics, it needs to mean this: when one person proposes an idea, if someone else has a better idea that more people will like, the better idea should win the day. In effect, if you have a bill you want to pass, but I have an amendment that the majority thinks would make the bill better, then my amendment should be incorporated into the bill. That, in legislative life, is deliberation: a new idea having the chance to be voted on to replace an old idea, and actually replacing the old idea if the majority likes the new idea better. Normatively, this is what we want: people continually propose modifications to law, and the legislative output iteratively develops to ultimately match the will of the majority.

And when you come around to that version of deliberation — rather than one based on people listening when other people speak — all of a sudden the Senate does begin to resemble the world’s most deliberative body. Generally speaking, amendments cannot be restricted on the floor without unanimous consent; anyone who thinks they have a better idea is guaranteed a vote on that idea to see if the majority agrees with them. No one can get their own idea passed into law without the possibility of a better idea replacing it. This is the essence of the Senate at its best — there’s no way to lock the place down and ram through your ideas, if the majority wants a different idea.

But wait, in what sort of oddball legislature would they allow the opposite — ideas getting passed into law that a majority wants to, but can’t, amend with better ideas? Oh wait, that’s the United States House of Representatives! In the House, the majority can write restrictive rules of debate for individual bills, rules which state what amendments are and are not allowed to be voted on. The majority leadership routinely uses special rules, held together by partisanship and punishment for dissenters, to eliminate the possibility of popular amendments altering the leadership’s ideas in any way.

This isn’t an occasional thing, either — the vast, vast majority of important legislation goes through the House under a special rule, and a fair percentage of the time there is a plausible amendment out there which would have majority support in the chamber, but cannot be proposed because the leadership has excluded it from the special rule, and has held together the majority party on the special rule vote through carrot and stick tactics with the backbenchers. And this has been a recent development. Even as recently as 30 years ago, most important bills came to the floor under open rules, or at least allowed a wide variety of amendments. Now it is virtually zero.

I say this all because the general public consensus is that the Senate is broken. But if your concern is democratic deliberation, in the true legislative output sense of the word, the House might be your real worry.

All that said, there is a procedural way for the majority leader to at least partially shut-off undesired amendments in the Senate, known as “filling the tree.” This procedural tactic, although still relatively rare, has come into greater use in recent Congresses. And from a deliberative point of view, it is not unrelated to the value of the filibuster: if minority-offered amendments can be eliminated procedurally, then one of the key arguments in favor of the filibuster is undercut. For if the filibuster cannot be used to secure the right of minority amendments, then it is largely reduced to just an up/down supermajority hurdle on the passage of legislation, which is a much weaker (albeit, still defensible) justification for its existence.

So let’s talk through filling the tree in the Senate. It’s a nice way to do a basic refresher on some Senate amendment procedures, too. There’s a ton to talk about here, so let’s do it Q&A style.

Q: What prevents House-style special rules from being written in the Senate to restrict amendments?

A: Unlike under the House rules, the Senate rules do not allow a bare majority to change the rules at will. So while the partisan majority in the House can (and routinely do) write temporary rules to structure debate and limit amendments, in practice the Senate can only do so by unanimous consent. Which they do, all the time. But if they can’t come to a unanimous consent agreement to structure the debate on a bill, then they have to go by regular order.

Q: What does “regular order” entail?

A: It just means that they have to go by the actual Senate rules, rather than whatever they would make up in a unanimous consent agreement. For this discussion, there are two key features of regular order:

1) Unlimited debate. It is well-known that under normal Senate rules, debate on certain motions cannot be stopped against the will of a Senator without a supermajority for cloture.

2) No restrictions on germaneness of amendments. The normal Senate rules (unlike the House) allow a Senator, in most situations, to offer an amendment on any topic at any time.

Q: Wait, non-germane amendments are allowed in the Senate?

A: Yes. This can often lead to debate on a bill ceasing to be about the bill itself; instead, the entire debate shifts to debate over an amendment. The minority is quick to take advantage of this — the democrats were famous for offering minimum-wage amendments to everything under the sun in the late 90’s Republican-controlled Senate. Just yesterday, the Blunt amendment regarding health care coverage of contraception was a non-germane amendment to the Highway reauthorization bill.

Q: So any Senator can offer any amendment on any topic at pretty much any time?

A: In theory, yes. And this is what makes the Senate so different from the House. You can take an entire bill — one that the majority has no intention of ever bringing up, or even letting out of committee — and put it into an amendment and then attached to any piece of legislation. There are four major exceptions, in which amendments must be germane: appropriations bills; legislation raised under the Budget Act or other laws that specifically require germaneness; amendments made after cloture has been invoked; and, of course, when a unanimous consent agreement has been reached that restricts non-germane amendments.

Q: So Senators can just keep adding amendments to a bill, forever?

A: Yes, but not exactly. Absent a unanimous consent agreement and short of getting cloture, debate on any bill or amendment cannot be limited. However, the amendment process is still structured. That is, under regular order, only a certain amount of amendments are allowed at once, and they must be disposed of before further amendments can be offered. In addition, there is a limited number of opportunities to amend the same piece of text in a bill. So there’s no cap on the number of amendments, but you do have a process that both eventually runs out of room for amending, and also limits the number of amendments that can be pending at one time. And this is the key to filling the tree.

Q: Why is it called “filling the tree?” What’s the tree?

A: The amendment process in the Senate is quite complicated. In order to simplify it, a set of charts have been developed by the parliamentarian to make it easier to understand when and what type of amendments may be offered. These charts are known as the “amendment trees,” due to their likeness to a tree trunk and branches. “Filling the tree” is the term for using up all the available amendment branches.

Q: How is the amendment process structured?

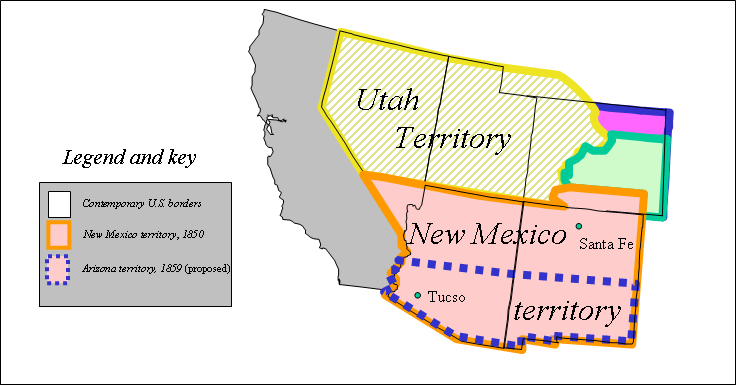

A: It depends on what form the underlying legislation comes to the floor, as well as what kind of amendment is first offered. I’ll use the most simple example here, a motion to insert text into a bill. Here’s what the amendment tree looks like:

Under the Senate rules, when someone offers a 1st degree amendment to insert (“A” in the chart), no other 1st degree amendment to the bill are allowed until the pending amendment is disposed of. However, a 2nd degree amendment can be offered to amend the either the 1st degree amendment, either a perfecting amendment (“C”) or a substitute amendment (“B), or both if the substitute is offered first. (Generally speaking, a 2nd degree substitute amendment would replace the entire 1st degree amendment, while a 2nd degree perfecting amendments alters the text of the 1st degree amendment.)

Q: Huh?

A: It’s not as complicated as it sounds. Say we have a bill that “requires all school lunches to include fruit.” I offer a 1st degree amendment to insert “and vegetables.” Someone else then offers a 2nd degree substitute to my amendment that says “and whole grains,” which would have the effect if adopted of removing the “and vegetables” and replacing it with “and whole grains.” Finally, someone offers a 2nd degree perfecting amendment to my amendment that inserts “green” before “vegetables,” which would have the effect of making the amendment “and green vegetables.” There you go. One important issue is the order of voting. In the case of a 1st degree amendment to insert, the vote order is 2nd degree perfecting, 2nd degree substitute, then 1st degree insert (as labeled 1,2,3 in the chart). And that has all sorts of strategic consequences. For instance, if the perfecting 2nd degree amendment that inserts “green” is popular, then the original 1st degree amendment (for just inserting “vegetables”) will never get a vote, since once it comes up for a vote, it will read “green vegetables.”

Q: But if there are limited amendments allowed, how come there are often dozens of amendments pending in the Senate?

A: Two reasons. First, that’s just the most simple amendment tree. In other scenarios (for instance, when the original 1st degree amendment is not an amendment to insert), you could have up to 11 1st and 2nd degree amendments pending. But more importantly, amendments can be laid aside in the Senate by unanimous consent, meaning that multiple first degree amendments to insert could be pending if everyone agrees to it. In fact, once you fill the tree, you have to make sure to object to any unanimous consent request to allow further 1st degree amendments, since that would of course make them available.

Q: So how do you fill the tree?

A: It’s easy: you just offer amendments on all possible branches, until no more amendments are allowed. At that point, no further amendments can be made until your amendments are disposed of.

Q: When do those amendments come to vote?

A: Unknown. Remember, there is unlimited debate in the Senate under regular order. Once the 2nd degree perfecting amendment is pending, no further amendments are allowed, and the vote on the 2nd degree perfecting amendment will not occur until debate has ended.

Q: But won’t those votes eventually happen?

A: Yes, but if you keep debating, the votes might not happen until after cloture is invoked on the underlying bill.

Q: Why does that matter?

A: Because, as we discussed above, after cloture is achieved, only germane amendments are allowed. So any non-germane amendment that a Senator had hoped to offer prior to cloture is no longer eligible.

Q: And therefore, the majority can limit the amendment process to germane amendments?

A: That’s right. And they can theoretically do more than that. Since there’s a finite amount of debate time allowed post-cloture, the majority could fill the tree, get cloture on the underlying bill, and then run out the clock post-cloture debating the existing amendments, never letting any other amendments be called up. And they could make all the amendments trivial, such that the vote on them doesn’t even matter, since it won’t change the underlying bill.

Q: But couldn’t minority Senators do the same thing, and fill the tree with friendly amendments?

A: No, for two reasons. First, amendments can be disposed of negatively prior to the end of debate; it’s called tabling. Anyone who gains the floor may make a motion to table an amendment, even if debate on the amendment is not complete. And the motion to table is itself non-debatable. Therefore, unpopular amendments can be quickly disposed of. This, of course, makes logical sense: there is good reason to allow extended debate on something the (numerical) majority is trying to pass; there’s not a lot of reason to allow extended debate on something a (numerical) majority opposes and doesn’t want to talk about.

Second, by practice and precedent, the majority leader has the first right of recognition on the Senate floor if multiple Senators are seeking recognition to offer amendments. Under Senate rules, a Senator who offers an amendment not only loses the floor after offering it, but also may not offer a 2nd degree amendment to the amendment until action has been taken on it. Now, the latter problem could be solved by asking for the yeas and nays (which doesn’t relinquish the floor), but it still requires gaining recognition multiple times in a row. Only the majority leader can realistically hope to achieve that, since he can block any attempt by another Senator to do so (as could the minority leader, or bill managers, who have priority after the majority leader.)

Q: But why do that. Why not just table the non-germane amendments you are trying to keep out?

A: Three reasons. First, you might not have the votes. If the Senate is closely is divided, say your majority has a 52-48 advantage, then your caucus might be against a policy by a 49-3 margin, but unable to prevent passage of the amendment. So, just like in the House, you might prefer to never have to deal with it. You can use various bargaining tools to persuade your 3 supporters not to bring it up, and those same tools might work on the minority, but if they don’t then filling the tree might be your best way around having to include the amendment. And no, you can’t really filibuster the amendment, since that will stop your underlying bill dead in its tracks, which is probably just fine with the minority.

You also might be facing a killer amendment (also known as a “poison pill”). Killer amendments are simple: they are minority amendments that split the majority into two camps: one group that can’t possibly vote against the amendment, and a second group that can’t possibly vote for the underlying bill if the amendment is included. The minority then votes strategically: they vote with the first group to pass the amendment, and then they vote with the second group to kill the bill. Example: gun control. Say there are 48 Republicans, all who support a gun rights amendment. And say there are 15 Democrats who also support it, and must vote for it. But there are also 15 Democrats who can’t ever vote for a bill that includes strong gun rights. The GOP offers the amendment, it passes with 63 votes, and then the bill fails when the GOP aligns with the other 15 Democrats to vote against it. Filling the tree can theoretically avoid this situation.

The third reason is that, even if you have the votes to table an amendment, you might not want to take the vote. Minority amendments are often raised in an effort to put the majority on the record either supporting or opposing particular policies, and in many cases the majority would simply prefer to not go on the record, at least not in bill language chosen by the minority at a particular point in time.

Q: So how does this actually work, in practice?

A: Typically, it’s a move of last resort. The majority almost always prefers to call up bills and structure the debate and amendments under a unanimous consent agreement if they can get one that satisfies them. It’s just faster and more predictable. But short of that, the majority leader will get the bill on the floor (perhaps by securing a cloture vote on the motion to proceed), and then offer the necessary amendments, intervening between each to ask for the yeas and nays, until the tree is full. As an example, here’s Majority Leader Dole on May 3, 1996, filling a tree to avoid a non-germane amendment on the minimum wage [text is truncated by removing clerk readings, UC’s to dispense with amendment readings, and seconds for the yeas and nays]:

There being no objection, the Senate proceeded to consider the bill.

Mr. DOLE. I send a substitute amendment to the desk and ask for its immediate consideration.

The PRESIDING OFFICER. The clerk will report.

The Senator from Kansas [Mr. Dole] proposes an amendment numbered 3952.

Mr. DOLE. Mr. President, I ask for the yeas and nays

The yeas and nays were ordered

Mr. DOLE. Mr. President, I send an amendment to the desk to the substitute.

The PRESIDING OFFICER. The clerk will report.

The Senator from Kansas [Mr. Dole] proposes an amendment numbered 3953 to amendment No. 3952.

Mr. DOLE. Mr. President, I ask for the yeas and nays.

The yeas and nays were ordered.

Mr. DOLE. I now send a second-degree amendment to the desk.

The PRESIDING OFFICER. The clerk will report.

The bill clerk read as follows:

The Senator from Kansas [Mr. Dole] proposes an amendment numbered 3954 to amendment No. 3953.

And the tree is full. No more amendments allowed. Dole then explained his actions:

Let me also indicate, it is necessary to go through this procedure of filling up the tree so we can take action on this bill without having nongermane amendments offered to it. I would indicate we have made a proposal to the Democratic leadership with reference to minimum wage. I have asked Senator Lott to try to resolve that with Senator Daschle and others … if we want to change general policy, I suggest we do it through the process of hearings in the appropriate committee.

Q: Are there any loopholes?

A: Yes. The minority could offer a motion to recommit the bill to a committee with instructions to report back forthwith, which would be functionally the equivalent of an amendment. In order to avoid that, the majority leader would need to himself make a motion to recommit, and then fill that motion’s tree (which includes a first degree amendment and a 2nd degree amendment to the amendment). Senator Dole did this in the example above.

Q: Is it common to fill the tree?

A: Not particularly, but it’s more common than it used to be. During the 111th Congress, the tactic was used about 15 times. In comparison, it was only used twice in the 105th Congress.

Q: How does the minority feel about the tree being filled?

A: Um, they don’t like it. Not at all.

Q: What recourse does the minority have to the tree being filled?

A: Procedurally, very little. Of course, the Senate is run on a lot more than procedure, and the minority can retaliate against perceived norm violations in all sorts of manners, ranging from withdrawal of support for some aspects of the bill at hand, to cross-issue retaliation, such as putting holds on other legislation or filibustering a nomination. And, of course, the minority can always escalate things by taking drastic actions, such as refusing to dispense with routine items by unanimous consent, such as the reading of amendments or even morning hour procedures such as the reading of yesterday’s journal. In effect, the recourse is largely political.

Q: Are there downsides to filling the tree.

A: Yes. When you shut off amendments, you shut off all amendments, including ones that your side might like to make. Now, that can be overcome in part by including those amendments as part of filling the tree, but that requires both forward knowledge as well as off-floor negotiation. And while that’s by no means impossible, it does highlight that filling the tree doesn’t simply preclude minority rights to amendments, it precludes everyone’s right to amendments.

Q: Are there other reasons to fill the tree besides avoiding non-germane amendments?

A: Sure. It can give the majority better control over the substance of amendments and the order in which they are voted upon. As noted above, the order of the amendment votes can alter which underlying ideas actually get a vote, as well as the pair-wise comparison that is being made in any given vote. Also, the majority can fill the tree as negotiating leverage if they are working with the minority on a UC agreement regarding debate or individual amendments.

Q: Is filling the tree a problem?

A: Only if you think it is. But if so, then yes. As I discussed yesterday and earlier in this post, any legislature needs to draw a balance between the ability of the majority to quickly move its preferred legislation, against the rights of the minority and the individual to extended debate and deliberative amending of legislation. In the end, these are both axiomatic sets of values, and your answer to the question of the propriety of filling the tree almost certainly depends on what underlying values you bring to the table. What filling the tree can accomplish — shutting off non-germane amendments, and in some cases all amendments — is hardly beyond the pale for a legislature; after all, the former is written right into the rules in the House, and the latter is accomplished in the House on a daily basis. But, while perfectly legitimate procedurally, it certainly is not in the spirit of the traditional Senate rules.

Previous “Q&A” style posts

December 15, 2011 — Rule Layover Waivers in the House.

December 5, 2011 — How a bill becomes a law. Literally.

November 29, 2011 — The other caucuses. The ones in Congress.