A lot is being written this week about Authorizations for the Use of Military Force (AUMFs), in part because of the recent military attack on Syria and in part because Senator Corker (with Senators Kaine, Flake, Coons, Young, and Nelson) introduced a joint resolution AUMF (S.J. Res 59) in the Senate to repeal and replace the existing 2001 terrorism and 2002 Iraq AUMFs. Here’s a good primer on the Corker legislation. Here are good CRS reports on the difference between an AUMF and a declaration of war (mostly how they trigger other emergency laws), issues in the continued use of the 2001 AUMF, and issues surrounding a new, replacement AUMF. If you want to dive into the endless debate over the division of war powers between Congress and the president, you can head over to lawfare or read Lou Fisher’s primer on it. The rabbit-hole follows from there; armed with wi-fi and some patience, you will never find yourself wanting for another opinion about American war powers.

In this blog post, I’m going to make four structural points about war powers that I think generally get overlooked in the public debate.

First and foremost, warmaking is decidedly a political issue and not a legal one. You can’t swing a dead cat on the political internet right now without hitting someone claiming the Syria attacks were “illegal.” Members of Congress. Law professors. Foreign leaders. And so on. But almost all of these claims and their intricate arguments mistake the nature of war power under the Constitution: it is fundamentally a political question.

No federal court is going to step in and adjudicate the fundamental question of going to war; despite evidence that courts were willing to take up at least some of these questions in an earlier time, since the Vietnam War it has largely become Court doctrine that questions of war powers are best settled by the political branches.

There’s a lot of nuance here, particularly if the president were to explicit violate another part of the Constitution (by, for example, spending money that Congress had specifically and affirmatively declined to appropriate), but Area Congressman Annoyed That Courts Won’t Grant Him Standing To Argue President’s War Unconstitutional is more or less a 40-year running Onion headline at this point.

How do the political branches adjudicate control over the war power? By using their constitutional authorities to assert power and constrain other political actors, and by lobbying the public to politically and electorally weaken their opponents. The president can order military strikes. Congress can fund or not fund the military. The president can veto or sign such funding limitations. Congress can pass or not pass AUMFs. The president can rally the public in favor of war if Congress won’t pass an AUMF. Congress can rally the public against the president if they believe he is going to (or did) launch an unwanted or unnecessary war. The president can abide by the War Powers Resolution reporting requirements or not. Congress can impeach him if he ultimately refuses to listen. (See Matthew Dickenson’s recent blog post for a bit more of this.)

Within this framework, arguments about the “legality” of a war aren’t worthless, but they also don’t serve a legal role. They become political arguments designed to sway public opinion. Again, political actors have two tools available to them in these kinds of fights: their formal powers and their persuasive powers in the public sphere. As Josh Chafetz has written, it is the judicious use of both of these powers that ultimately settles political fights.

Second, that warmaking is political doesn’t render AUMFs (or the War Powers Resolution) useless. One response a lot of people have to this political conception of the war power is to just throw their hands up and say that the AUMFs are useless, since the president will just do what he wants, claim inherent war power under Article II of the Constitution, and Congress will never dare to use their hard power to cut off funding for troops in the field.

I think this is exactly wrong, on all counts. Presidents are generally very attune to public opinion about war, with good reason: unpopular wars are among the most deadly things for presidential approval ratings and reelection chances. When Congress is unwilling to provide an AUMF for a particular military action, that is both a signal to the president about the popularity of a theoretical upcoming military action and a signal to the public that not all political actors are on-board with the proposed action.

And while the lack of an AUMF might not stop a president from launching some sort of strike, it has almost certainly constrained presidents as to the scale and scope of military actions. Presidents are simply loathe to launch wars on their own; this is why they go to Congress and the public to preemptively build cases for such actions. Whatever its merits, Bush painstakingly built a case for the Iraq War. Obama’s action in Libya were highly constrained by a skeptical Congress and public. And the same is currently true for Trump and Syria.

Second, it is simply not true that presidents ignore congressional statutes in regard to war. As much as they can moan and complain about the War Powers Resolution, every president has complied with its notification requirements. Defense Secretary Mattis testified in strong opposition to a revised AUMF that limited the geographic scope of the war on terrorism, precisely because the administration would feel compelled to follow such statutory limitations on their authority. Again, they could always go beyond the scope and claim Article II authority to do so, but the public cost of doing that would be high.

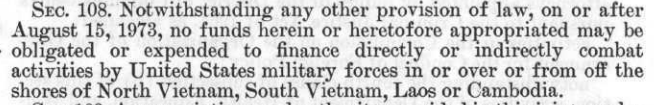

We have also not observed presidents defying the hard authority of Congress over war funding. Many people mistakenly believe Congress would never cut off funding in order to stop a war, but such limitation riders in appropriations bill have been used successfully numerous times. Most famously, the Vietnam was was first limited (by preventing expansion to Cambodia) and then effectively ended through limitation amendments.

More recently, such limitations were placed on U.S. military activity in Somalia and Rwanda. In all of these cases, the president complied with the congressional restrictions. For a more detailed look at funding cutoffs, see this CRS report.

Third, the Constitution creates a strong status quo bias in public life in the United States. It’s not exactly breaking news that the U.S. constitutional system is designed to produce inaction absent substantial consensus. The separation of powers system was put in place by the Founders specifically to prevent accumulation of power in any one person or institution, and to give the various institutions incentives to struggle against each other.

The large number of veto points in the system make it difficult to create public policy change even with super-majority public support. The status quo almost always wins in American public life. The flipside of this status-quo bias is that once you do achieve public policy change, it becomes equally difficult for opponents to reverse it. In effect, your change becomes the new status-quo.

This creates a distinctive problem for Congress in regard to statutory presidential powers. Congress can give the president new statutory powers by gathering a majority vote in the House and a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate. But once the president is given such powers, Congress will need a 2/3 supermajority in both chambers to repeal them, since the president will almost certainly veto any attempt to reduce his statutory authority.

In effect, the status quo bias within the constitution is assymetric and tilts toward the presidency; I call this the “ratcheting-up effect.” Disrupting the status quo to provide presidential power is far easier than disrupting it to limit presidential power.

What Congress does have on its side is the ability to design and craft policies that expire. If purposeful congressional action is required to continue a policy, the constitutional leverage over the policy shifts from the president to Congress. This is how discretionary appropriations work. The money runs out in the executive branch (most appropriations last one fiscal year), and the president needs to come ask for more. If Congress does not actively provide them, the account goes unfunded. The heart of the power of the purse isn’t really that Congress controls the money, it’s that the money runs out and Congress needs to positively act to provide more.

In regard to statutory presidential powers not derived from appropriatoins, Congress can create such expiration by using sunset clauses. These are provisions that specify the legislative grant of power to the executive ends at a date certain. This way, Congress never has to face a supermajority hurdle to repeal the authority; they can simply let it expire. If they wish to continue the policy/power, they can pass it again, under the basic majoritarian rules of the House and (relatively) mild supermajoritarian procedures in the Senate.

Lots of stuff is sunset by Congress. Parts of the PATRIOT Act were sunset. The TARP money was sunset. Virtually all appropriations are sunset to a year (even if the money doesn’t actually run out). Sunset clauses in legislation are strongly beneficial to congressional power. If you need proof of that, note how much presidents hate them.

Fourth, all AUMFs should be sunset. Period. The most important grant of authority Congress can give the president is a declaration of war or an authorization for the use of military force. Building a norm that all AUMFs be sunset would both strengthen congressional power and increase congressional responsibility over war, two goals that should be pleasing to citizens in a democracy.

First off, we should be very wary of giving war the benefit of the status quo bias of our constitution. War is not the normal condition of a well-functioning republic, and congressional decisions to end wars should not face higher hurdles than congressional decisions to begin wars. Presidents have numerous institutional temptations and incentives to prefer wartime, and thus Congress should retain the ability to choose when to start and stop wars with the least amount of presidential leverage.

Congress should never face the ratcheting-up problem regarding the authorization of war. Right now, presidents can and do point to an almost 17-year old congressional authorization as justification for military action abroad. That’s almost prima facie ridiculous. By sunsetting all AUMFs, Congress would force presidents and others seeking to continue wars to bargain without the leverage of the status quo continuation of the war. As with appropriations, Congress would have the leverage, because inaction would cause expiration.

Second, sunset AUMFs would force Congress and the public to revisit the underlying authorization of war on a regular basis. This would require new Members of Congress to go on record supporting an existing AUMF if it was to be renewed, and would offer opponents of the AUMF an opportunity to amend it or simply fight to not renew it. Only 96 of the current 435 Members of the House of Representatives and 23 of the 100 Senators were in Congress when the current 2001 AUMF against terrorism was voted on and passed. A sunset provision that regularly required Congress to renew authority for an ongoing war would create an environment in which representatives would need to justify a decision to continue a war. Not all policies should require such continued justification, but if any do, it seems like war is a good candidate.

What should an AUMF sunset look like? There are lots of suggestions floating around both Congress and the public sphere right now. Jack Goldsmith likes a 3-year sunset. That seems fine. I’d prefer all AUMFs be linked to the current Congress, and expire 60 days after the start of the next Congress. That would give the new Congress plenty of time to debate and consider an extension. Or not. But it would enshrine the principle that continued war is a decision made by Congress, as well as a responsibility of each Member of Congress to take on.

There is strong opposition to this right now. Some of it is substantive—Members of Congress or the public who want the war on terrorism to continue unabated in its current form have little incentive to build a general sunset norm around AUMFs or support a specific sunset for the current 2001 AUMF. Some of it is a belief in presidential war power; certainly the administration is very much against any time limitations in AUMFs, and they have allies in Congress as well. Other members of Congress may be happy to shirk responsibility over war to the president; by maintaining an old AUMF they gain the ability to criticize the president when POTUS starts a war that goes badly, without having to accept responsibility for authorizing it. Congress is not totally innocent here.

But in some ways they are. No one imagined that the 2001 AUMF would still be in force today and be the basis of presidential actions in dozens of countries. It seemed relatively targeted at the time, given its plain-reading scope that associated it with the 9/11 attacks. A never-ending AUMF is not the nasty “emergency powers” often granted to dictators in pseudo-democracies around the world, but it does feel vaguely in the same category.

Opponents would have you believe sunsetting an AUMF is equivalent to telling our adversaries when we will stop fighting. This strikes me as ridiculous. No one questions the sunsetting of the PATRIOT Act surveillance provisions on these grounds. And no one questions the annual nature of military appropriations on these grounds. There is also precedent for sunsetting an AUMF. The 1983 AUMF for action in Lebanon was sunset to 18 months.

It is true that Congress holds the power of the purse, and that an end to any war can be achieved in that manner. In the grand sense, the president can only fight with the army Congress builds him. And limitation amendments on appropriations can effectively be used to constrain or end conflicts, and have been. But a sunset AUMF is as much about restoring Congress’s role in the debate over a continuing war as it is about restraining the president’s leverage over such authorizations. And no committee markup or floor debate about a limitation amendment can substitute for a full discussion about the continuation of an AUMF. In some ways we are seeing that right now with the Corker joint resolution. It would be a much better situation if we saw it every two years.