Back when I was in graduate school, my (dorky) friends and I had an impromptu contest: everyone had to create an urban legend based on their dissertation research, and whoever could spread it the farthest on the Internet in 1 month won. Since my thesis was about statehood politics, I came up with the following: a DC statehood bill passed the House in 1984, but stalled in the Senate because a Reconstruction-era Supreme Court ruling requires that all U.S. flags flown by the federal government or a state government be up-to-date, and thus DC statehood would have meant the tremendous cost of going back to the moon to update the 50-star flags we planted there. I always kinda liked that — it’s stupid enough to make you laugh, but just plausible enough to possibly make you think twice.

And while that’s just some throwaway humor, I have always thought the connection between statehood and the flag was somehow important, enough so that the original title of my dissertation — and the title I’ll probably use if it ever becomes a book — was Sewing New Stars. The U.S. flag almost perfectly reflects the dual-sovereignty of our federal system: the states are constituitive of the whole, but the whole is far greater than the sum of its parts; and when we add a new semi-sovereign state to the union, the flag itself changes, a lingering physically manifestation of a fundamental political action within the federal union. And the post 1818-flag — in which the number of stripes is fixed at 13 — reflects a wonderful understanding of the union: new stars can be added to the union, but those new stars, rather than fundamentally altering the union, instead simply become part of it. The union itself, like the stripes, is perpetual and unchanging.

And yet that’s just so much romantic hogwash.

The more important connection between the flag and statehood —and I say this only three-quarters jokingly — is political, as in raw political power. As in currently-untapped raw political power. Let me explain.

One of the animating principles of democratic theory — whether your favorite political theorist is James Madison or Barry Weingast — is that human beings are self-interested, and that self-interest will motivate their political choices. Furthermore, the working assumption for at least the last few centuries is that the primary self-interest for most people will be economic. Which is to say, most people will make their political choices based primarily on the impact those choices will have on their accumulation of the scare material resources of society.

There are all sorts of well-known individual and collective consequences of this, ranging from the tendency of democracies to create inter-generational externalities (pushing pollution and debt costs onto our children) to the difficulty of forming interest lobbies for large groups seeking diffuse benefits (why spend the money to join the Sierra club when you can just free ride and get all the benefits?).

This is not to say that people will not, on occasion, be motivated by the common good (like reducing poverty) or by interests that are not primarily economic (like reducing abortions). But for most people most of the time, those interest will be secondary. Especially if they come into conflict with the economic self-interest. Which is simply to say that your views on the proper future of slavery circa 1857 might well have hinged on the amount of capital you held in slaves, or the degree to which your livelihood was dependent on the slave economy.

This, of course, can make for some interesting situations, in which economic self-interest puts people or groups in awkward moral situations. The most famous (and potentially disturbing) example is the role of munitions makers in the promotion of war. This has been a popular concern for centuries, and nary a major war occurs in which the weapons manufacturers aren’t accused of promoting and/or outright lobbying for conflict over diplomacy. A more humorous example is the often-told dark joke about segregation being propped-up politically by the deep pockets of the water-fountain manufacturers lobby. And if you happen to own the equipment needed to clean up an oil spill, well, yes. There does not seem to be an issue one can think of in which an economic interest for somebody can not be imagined.

Which brings us to the flags. As you might suspect, I have a certain fascination with the modern statehood movements in Puerto Rico, DC, and other American territories. Most of these movements have almost zero chance of success. Besides the mixed merits of their substantive claims for statehood, many of the movements are chronically underfunded,. There’s little incentive for the average person — either in the territory or outside of it — to donate money to them, because of the lack of particularized benefits and thus the ability to free-ride. Similarly, the economic consequences of statehood (in the contemporary cases) do not obviously benefit any sectors of the economy in particular. So the incentives for industry are at best neutral in regard to statehood, or in some cases may theoretically be to work against it. In other words, there doesn’t seem to be anyone to bankroll any of these individual movements.

But there is one potentially large, national interest group that seemingly has a huge stake in the success of any and all statehood movements: flag manufacturers!

Think about it: the average flag never needs to be replaced (not counting the little throw-away flags used at 4th of July or whatever). They basically last forever, or at least a solid 40 years. So the demand for flags is almost purely based on the need for flags in new locations, with very little demand based on life-cycle replacement of existing flags. But if a 51st state were to be admitted to the union, every flag in America would need to be replaced. Every classroom in America, every government building, all the military flags, every patch on every college basketball jersey, all the 4th of July sidewalk lining flags that reused every year. Hell, as described above, there are 50-star American flags on the moon. It’s endless!

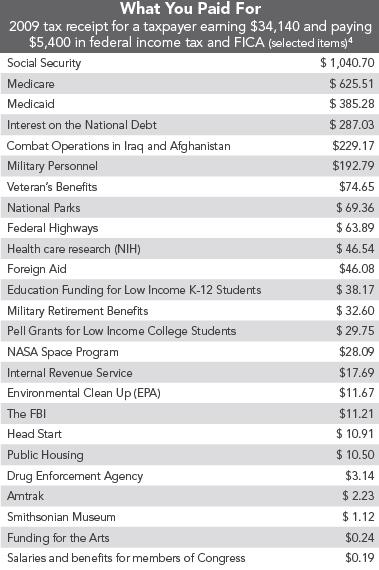

Let’s do some very rough back-of-the-envelope math to figure out what kind of cheese is at stake here. Flags cost all different prices, but it looks like your basic nylon mid-size U.S. flag is something like $20. I have no idea what the profit margin is on a flag, but I don’t think $2-$5 is unreasonable. Let’s say $2.50 per flag. Now we just need to know the total number of U.S. flags to be replaced. Who the hell knows? It’s like one of those i-banking interview questions. Five hundred thousand? A million? 50 million? I literally have no idea. But we need a better answer than “a mind-boggling amount.”

So let’s just estimate a sub-question: how many flags would the public schools need? Let’s assume that there’s a flag in every classroom, as there was when I was growing up. A quick google search indicates that no one actually knows how many high schools there are in America, but various estimates seem to be around 20,000. Give each of them a radically conservative estimate of 15 classrooms. And give each high school one middle school and 3 elementary schools with a total of 35 more classrooms. By my math, that’s a million flags right there, in a conservative estimate. Which tells me this might be a billion dollar issue. In an industry that (evidently) hasn’t had a boom year since, well, 1959.

And talk about a manufacturing-sector stimulus plan. Imagine what the DoD contract for all new flags is worth? The lobbying campaign almost writes itself. Expand American Freedom, Create American Jobs. Do your part: give the gift of America this year. Statehood: It’s not just a 19th century relic. It helps makes the U.S. economy strong.

Of course, the flagmakers shouldn’t be satisfied with just a 51st state. The best strategy for the flagmakers’ lobby would be to try to get a state admitted about once a year, preferably in the late Spring. Under the flag laws at 4 U.S.C. § 2 (yeah), regardless of how many states are admitted to the union in a given year, new stars are only put on the flag on July 4, meaning it’s worthless for the flagmakers to get two states in at once. And the closer the admission date is to the next July 4, the less chance of any competition sprouting up to manufacture flags during the windfall. If you already are in the business of flagmaking, and you could just get a surprise admission in mid-June each year, I’m pretty sure that’s a goldmine.

Perhaps next week, I’ll do a more serious post on DC statehood. But for now, let me say that my preference would probably be to repeal the 23rd amendment, shrink the federal seat of government down to the bare-bones area surrounding the Mall, the White House, and the Capitol, and retrocess the remainder of the district to Maryland.