[condensed from an academic piece I’m working on…]

Historians and political scientists have long viewed the civil war and its aftermath as a formative period of American political development. Across numerous dimensions of political life, the United States was radically altered between the beginning of secession in 1861 and the end of Reconstruction in 1876. Rights of citizenship, the structure and role of the military, the relative power of the presidency, taxation policies, and the structure of the party system were all strongly affected by the war. And decisive answers were obtained for two pressing questions of the first half of the 19th century: what was the future of slavery and does the ultimate authority within the federal system lay with the federal government or the individual states.[1]

There is also a sense that wars, in general, are likely to have dramatic effects on the development of politics within a nation.[2] Throughout American history, wars have served as distinct moments of political change, as simultaneously the power relations of the federal and state government have shifted to address the necessities of war, while the wars themselves have altered the landscape underneath the feet of citizens and political actors.[3]

Here I discuss the development of the political structure of the western United States – the creation of new states, as well as the territories that would become these new states – during the civil war and Reconstruction. Although the civil war Congresses are best known for their attempts to deal with the secession crisis and their management of the war, the tenures of the 36th-39th Congresses are also marked by the most rapid and consequential alterations to the political structure of the burgeoning proto-states of the American west: the creation of new territories, the geographic alteration of existing territories, and the admission of these territories as states to the union.

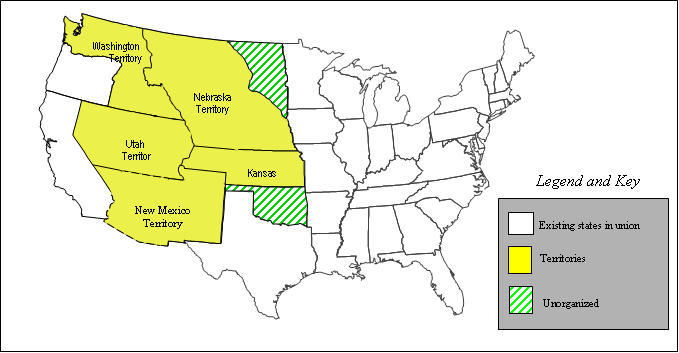

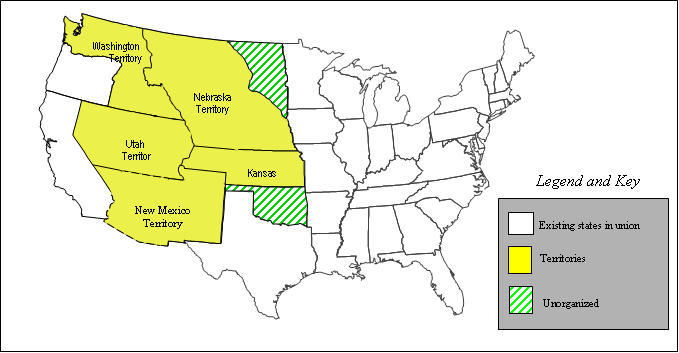

When South Carolina left the union on December 20, 1860, the American west consisted of two states (Oregon and California) and 5 large territories, all of whose boundaries would be unrecognizable to a modern observer (see Figure 1). By the close of 1868 – prior to the readmission of most of the southern states – the political geography of the American west had largely been transformed into its modern (and thus final) form: Nevada, Kansas, and Nebraska had been admitted to the union, and the remaining 11 (new) territories would undergo virtually no serious political alterations prior to admission to the union over the next 40 years, save for the division of Dakota territory in 1889. For all intents and purposes, by the time of Grant’s election in 1868, the underlying political structure of the continental United States was complete (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. The United States of America in 1860, by legal land status

Figure 1. The United States of America in 1860, by legal land status

Figure 2. The continental United States of America in 1868, by legal land status

Figure 2. The continental United States of America in 1868, by legal land status

Causes

Why did the war affect western political development at all? Fundamentally, the answer lies in the the structure of the statehood process in the Constitution. Among the various plans discussed between 1776 and 1787, the one that appears in the Constitution is by far the most radical — it provides for total congressional control, without any specific mandated guidelines such as population thresholds and square mileage requirements. Virtually every other proposed plan, including 19th century plans to reform the system, included such mandates. As a consequence, the constitutional structure made the process inherently and fully political, subjecting the long-term process of new state creation to the short-term push and pull of day-to-day politics. Issues and events that had a strong impact on the polity necessarily had a strong impact on western state development. The civil war – being perhaps the single most consequential event in American history – is no exception.

The secession of the south from the union in 1860-61, the military conflict from 1861-1865, and the Reconstructive period that took place from 1865-1876 are all examples of the contingent strand of politics that affected the formation and construction of new states in the west. Although it is not possible to conclusively determine the exact effects of secession, war, and reconstruction on the development of the west – we would need to know the contemporary political geography of the west sans civil war – we can identify through the historical record the actions which were made because of the war, and thus were unlikely to happen without the war. This sort of counterfactual thinking requires a certain degree of structure.

We can organize our thinking about these changes by asking a few questions: first, would the institutional change have occurred at all if it were not for the contingent event? A “no” answer to this question would result in the strongest claim that we could make about an institutional changes relationship to the contingent event. A good example from our list of changes made in the 1860’s is the admission of West Virginia to the union. Clearly, without Virginia’s secession from the union, this institutional change would never have occurred.

A second-degree question: would the institutional change have taken place in the identical form if it were not for the contingent event? A “no” answer to this question implies something like this supposition: the New Mexico territory of 1850 was likely to be divided at least once at some point prior to its becoming a state (or states). However, the decision to divide it with a north-south meridian instead of an east-west parallel was contingent on the civil war. Finally, would the institutional change have taken place at the time it did if it were not for the contingent event? This is the weakest claim, but not a trivial one, since the timing and sequence of these institutional changes are constitutive of the underlying structure of democratic aggregation in the United States, as well as highly consequential for the development of other future states and territories.

Again, although we can never be certain about any of these claims of contingency, one might expect that an event like secession and civil war would be most influential in the third class of effects (timing), somewhat influential in the second class (form), and least influential in the first class (direct consequence). And that appears to be the case with the 12 institutional changes that occurred in the 1860’s. Only West Virginia’s admission to the union can confidently be declared a direct consequence of the war that would not have happened otherwise. One additional change – the creation of Arizona – can confidently be said to be dependent in form on the war. And seven of the changes – the admission of Kansas, Nevada, and Nebraska, as well as the creation of Colorado, Nevada, Arizona, and Dakota territories – would not have happened when they did had it not been for the war. Only the creation of Montana, the redefining of Nevada, and the creation of Wyoming and Idaho seem relatively unrelated to the war.

We can classify the mechanism by which secession and war affected these institutional changes into three general groups: the secession of the south, worries about the secession of the west, and the desire to reinforce electoral victory in 1864 for the Republican party.

Secession

Ideological divisions over slavery had helped structure the politics of admissions to the union since almost the first days of the nation, and during the period from 1848 to 1860, slavery came to increasingly structure the politics of altering the territorial structure of the west.[4] After 1852, the political parties in the United States began to quickly drift toward an increasingly perfect correlation with the sectional division. By the 1857 fight over the Lecompton Constitution in Kansas, the deadlock in Congress over the alteration of the political structure of the west had become severe. Although two states (Minnesota and Oregon) were admitted to the union between 1857 and the beginning of southern secession, both of these institutional changes were aided by very precise political circumstances in the prospective state that led to barely-sustainable compromises to achieve their success. In the 35th and 36th Congresses (1857-1861), bills to organize new western territories were proposed and routinely defeated, both in and out of committee, by southern members of Congress and their (increasingly fewer) allies in the north.

Beginning December 20th, 1860 with the secession of South Carolina, the southern ideological wing of Congress slowly left Washington, D.C. By February 1st, 1861, they had lost a sizeable portion (and the most radical wing) of their voting power in the national government. In terms of policy output, this was the equivalent of an exogenous shock: although none of the existing preferences had changed about the organization of the west, only one side of a two-sided debate remained in the democratic assembly. Without opposition, they were free to act. And act they did. The Republicans in Congress enacted four major alterations to the west as quickly as they possibly could in the 2nd session of the 36th Congress.[5] In just over a month, they admitted Kansas to the union and created the Colorado, Nevada, and Dakota territories. None of these alterations would have been possible without the secession of the south.[6]

Fears of Western Rebellion

The second mechanism by which the war affected the process of institutional change in the west was through the general fear of a western rebellion and secession from the union. Although the exact nature of the relationship between the states and the federal government had been up for debate for almost two generations, the reality of the southern secession in 1860-61 quickly turned all of the theoretical arguments of the past 70 years into questions of immediate and concrete reality, including questions that had not been fully contemplated over the years: if the south was free to leave the union, was the west? If the south (free or not) did leave the union, did they have any claim over the western territories? If the north made peaceful disunion with the south, did that affirm the concept that peaceful separation from the union was both legal and attainable for other states, or for western territories? It is easy to see how these ideas made northern leaders, trying to hold the union together, quite nervous.

Of greatest concern to the union, however, was the competition with the south for the territories. There was no compelling reason to believe that the western territories, particularly political communities in the west that had been denied territorial status over the past decade, would side with the union in the war. The combination of these fears – the rebellion of the west into its own nation and the competition with the south for the allegiance and control of the territories – and the reality of watching their fears realized, spurred Congress into action during the war.

The creation of the Arizona territory is a good example. After the New Mexico territory was created as part of the compromise of 1850 (the Gadsden Purchase was added in 1853), there was a period of about 5 years where there was very little local or national voice for further division of the territory. Staring in 1856, however, residents of the southwestern portion of the territory living in Tucson began to petition Congress to divide the state along an east-west line. From 1857 until 1859, residents of Tucson annually sent a delegate to Washington from their proposed territory, but Congress refused to seat him. There were sympathetic politicians in Washington, particularly southerners eager to see the creation of new plausibly pro-slavery states, and bills were introduced in both chambers of Congress for the creation of Arizona annually from 1857 to 1860. Northern Republicans had little interest in creating a new southern-leaning territory, however, and correctly pointed out that the 1860 census revealed that Arizona county (the western portion of New Mexico territory) had only 6,482 residents, far too small a population to merit a territorial government. With the northerners firmly in control of the national government after the 1860 election, the prospects for Arizona territory looked slim.

The secession of the south, paradoxically, was just what Arizona needed. With the southern portion of the New Mexico territory largely a pro-confederacy population, territorial secession conventions took place at both Tucson and Mesilla in March of 1861. The conventions seceded the territory from the union, created a provisional territorial government, and sent out a petition to the Confederacy for admission.[7] By January, 1862, the Confederate States of America had passed legislation organizing the territory of Arizona, and had accepted a delegate from the territory to their Congress. Arizona was officially a political institution of governance, only it was now in the Confederacy.

The union did not wait to act. Lincoln dispatched the Army to occupy Tucson, and Congress prepared legislation in March to create the United States territory of Arizona. The decision was made to split the old New Mexico territory along a north-south line, in order to reduce the influence of southern-sympathizers in both the new territory as well as the (new) New Mexico territory, as well as to avoid the appearance of rewarding rebel communities in the west who might seek to organize future territories by seceding from the union. The legislation for the territory stalled for a bit in Congress, and Arizona territory was not officially created until February 24, 1863, long after the Union Army had retaken control of the area.

Manipulating the 1864 Election

The third mechanism that contingently affected western institutional change during the civil war era was the desire of the controlling pro-war Republicans to ensure electoral victory in the 1864 election. This contingency has been well-documented.[8] By the spring of 1864, disillusionment in the North with the progress of the war had emboldened the Democrats to support a platform of peaceful settlement with the south, and they had nominated a candidate, General George McClellan, who was committed to ending the war. The Radical Republicans in control of Congress saw the reelection of Lincoln as absolutely vital to preserving the war effort.

Admitting additional western states to the union prior to the 1864 election could potentially put Lincoln over the top if the election were close. Although any newly admitted state would likely have a low population, the new state would have at least the guaranteed minimum of three electoral votes, and that could make the difference in a close election. The admission of Nevada to the union is relatively well-known as the best example of a short-term electoral incentive shaping a state admission to the union.[9] Nevada’s population in 1864 was a paltry 6,857, far fewer people than any of the other existing western territories save Dakota. Still, Nevada would stand to be the most reliably Republican state of any of the territories if it were admitted to the union prior to the 1864 election. In addition, the Republicans saw other advantages in the admission of Nevada: it might increase their chances of holding onto the Senate, and it also would add another state inclined to vote for passage of the 13th amendment.[10]

Consequences

At the time of the final readmission of the southern states to Congress in 1870, the political structure of the American west looked completely different than it had just 10 years earlier. The rapid pace of western institutional change, combined with the utterly contingent nature of many of the changes, had created a continental political structure whose details could hardly have been fathomed by even the most creative political thinkers of the 1850’s. Even more startling, from the perspective of national politics, was that the entire political role of the territories for the previous 25 years – as the explosive sideshow setting where the factions of the national slave debate could engage each other – had ceased to exist with the military defeat of the Confederacy and the passage of the 13th amendment barring slavery. Whatever the civil war did to change the nation, its final resolution profoundly closed one chapter of American territorial history, without anyone clearly seeing what was to come.

Numerous historians of the American west have noted that the contours and features of the territorial system in the first half of the 19th century were dramatically different than the features of the system after the civil war.[11] The disappearance of the slavery issue, the rise of the west as a section with a distinct political interest, and the hegemony of the Republican Party’s control of the national government all served to radically alter the place of western institutional development within the national political context. For the average citizen, the disappearance of the slavery issue had rendered the importance of the territories near nil. To the national politicians of both parties, the prospect of using new western state admissions to bolster their partisan numbers had to be tempered against the ideological cleavages that pitted westerners against the interests of both the northern Republicans and Southern Democrats. Without the stability of the slavery issue (as discussed in chapter 6), use of the territories as sectional leverage became much more risky; the signal had become noisy. And to the ruling Republican Party of the late 19th century, the western territories seemed more useful as sources of patronage than as prospective states.

One consequence of this that could not have been foreseen during the rapid developments of the 1860’s was the sheer finality of the enterprise. After 1870, there were virtually no adjustments to the boundaries of the existing territories, and no territories were created, save the division of the Dakota territory into North and South just prior to statehood.[12] Over the next 43 years, these territories were admitted to the union as states. But their final boundaries – indeed, the final contours of the American federation – were the ones drawn in the middle of the civil war. The exogenous shock of the war led to a highly contingent development of the western political structure, and the cataclysmic changes that the end of the war brought upon American national politics served to solidify those changes into place.

A second consequence of these rapid and contingent changes made to the western political structure was a certain amount of buyer’s remorse, both locally in the territories and also among national politicians. The Republican Party, prior to the war, had long sought to encourage western migration and the political development of the western territories, as these types of things both naturally fit with their free labor, free soil ideology while simultaneously creating more Republican voters and new Republican states. The push to create the new territories that began and the late 1850’s and succeeded after the secession of the southerners was driven in part by a desire to enlarge a coalition that, by 1870, had in many ways ceased to exist. Without the anti-slavery narrative, it became more obvious that western Republicanism was differentiable from Northern Republicanism on a number of key issues, notably silver.[4]

The emergence of a third economic section of the country presented a new wrinkle to the statehood politics of a two-party system. The addition of a new western state to the union was far less palatable to the existing states when the benefit was reduced from a permanent vote against slavery to a partisan agreement on the speaker, but certain differences on economic policy. Republican enthusiasm in Congress for the admission of new states, even Republican-leaning states, waned in the wake of the civil war. The prospect of further dividing the existing territories, and thus creating even more potential western states, was unpleasant, if not unthinkable. Indeed, bills put forth in Congress in the 1870’s were just as likely to suggest shrinking the number of western territories – through the abolition of one or more and the expansion of the others – as they were to propose the division of territories into new potential states.

In the territories themselves, the buyer’s remorse evidenced itself somewhat differently. Here, the politics was local, and the rush to create territories in the previous 15 years in what had been relatively unpopulated areas led to a somewhat incongruent set of political communities. This was exacerbated by the unwillingness of Congress to alter the territories during the late 19th century. This is not to say that efforts weren’t taking place to alter the structure of western government. To the contrary, the House and Senate committees on Territories were kept busy with a steady stream of petitions arrived at Congress between 1865 and 1880 asking for either the division of a territory, the rearrangement of territorial boundaries, or the admission of territories as states to the union.[13]

Notes

[1] Eric Foner and American Historical Association.,

Slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction ([Washington, D.C.]: American Historical Association, 1997), David Morris Potter and Don Edward Fehrenbacher,

The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, 1st ed.,

The New American Nation Series (New York: Harper & Row, 1976).

[2]David R. Mayhew, “Wars and American Politics,” Perspectives on Politics 3, no. 4 (2005).

[3] See Bruce A. Ackerman, We the People (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1991), Akhil Reed Amar, The Bill of Rights : Creation and Reconstruction (New Haven ; London: Yale University Press, 1998), Louis Fisher, Presidential War Power, 2nd ed. (Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas, 2004).

[4] See John Ashworth, Slavery, Capitalism, and Politics in the Antebellum Republic (Cambridge [England] ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995), Eugene H. Berwanger, The Frontier against Slavery; Western Anti-Negro Prejudice and the Slavery Extension Controversy (Urbana,: University of Illinois Press, 1967), Jesse T. Carpenter, The South as a Conscious Minority, 1789-1861; a Study in Political Thought (Gloucester, Mass.,: P. Smith, 1963), Arthur Charles Cole, The Irrepressible Conflict, 1850-1865 (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1934), Richard Patrick McCormick, The Second American Party System; Party Formation in the Jacksonian Era (Chapel Hill,: University of North Carolina Press, 1966), Roy F. Nichols, The Disruption of American Democracy (New York,: Collier, 1962), Potter and Fehrenbacher, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861.

[5] The legislation was done quickly for a number of reasons, not the least of which was that the political environment was a great unknown, and it was not out of the question that a settlement of the secession crisis might happen prior to the end of the 36th Congress and the southern members of Congress might return to the chamber, and recommence their obstruction of western political development.

[6] And in one sense, they were a concession toward the south. The territories were all admitted without reference to slavery, a sticking point that had kept the north and south deadlocked for the previous 5 years.

[7] Paul L. Allen and Peter M. Pegnam, Arizona Territory, Baptism in Blood (Tucson, Ariz.: Tucson Citizen Pub. Co., 1990), Arizona. Legislative Assembly. and Anson Peasley Keeler Safford, The Territory of Arizona : A Brief History and Summary of the Territory’s Acquisition, Organization, and Mineral, Agricultural and Grazing Resources : Embracing a Review of Its Indian Tribes, Their Depredations and Subjugation : And Showing in Brief the Present Condition and Prospects of the Territory ([Arizona: The Legislative Assembly], 1874), H. C. Stinson, Arizona : A Comprehensive Review of Its History, Counties, Principal Cities, Resources and Prospects, Together with Notices of the Business Men and Firms Who Have Made the Territory ([Los Angeles: s.n.],, 1891), Microform.

[8] See Lauriston, “Abraham Lincoln and the Statehood of Nevada..”, Pomeroy, The Pacific Slope; a History of California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Utah, and Nevada, Charles Stewart and Barry R. Weingast, “Stacking the Senate, Changing the Nation: Republican Rotten Boroughs, Statehood Politics, and American Political Development,” Studies in American Political Development 6 (1992).

[9] Stewart and Weingast, “Stacking the Senate, Changing the Nation: Republican Rotten Boroughs, Statehood Politics, and American Political Development.”

[10] Earl S. Pomeroy, “Lincoln, the 13th Amendment, and the Admission of Nevada,” Pacific Historical Review 112 (1943).

[11] See John Porter Bloom, The American Territorial System; [Papers] (Athens,: Ohio University Press, 1973), Jack Ericson Eblen, The First and Second United States Empires; Governors and Territorial Government, 1784-1912 ([Pittsburgh]: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1968), Edmund Steele Joy, “The Right of the Territories to Become States of the Union” (Thesis Ph. D. –Columbia college., Advertiser printing house,, 1892), Lamar, Dakota Territory, 1861-1889: A Study of Frontier Politics, Gary Lawson and Guy Seidman, The Constitution of Empire : Territorial Expansion and American Legal History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), Earl S. Pomeroy, The Territories and the United States, 1861-1890; Studies in Colonial Administration (Seattle,: University of Washington Press, 1969).

[12] Even state admissions were not common. Referring back to figure 2, one can see that alterations to the political system were few and far between in the late 19th century. Between the 1868 and 1889, only one change was made – the admission of Colorado as a state in 1876. No other 20 year period in American history had seen fewer than 8 changes or fewer than 3 state admissions. Territorial politics continued in the territories, but the collective will in Congress seemed uninterested in any further development.

[13] For an excellent comparison of old and new state Republican views on Silver, See Stewart and Weingast, “Stacking the Senate, Changing the Nation: Republican Rotten Boroughs, Statehood Politics, and American Political Development.”