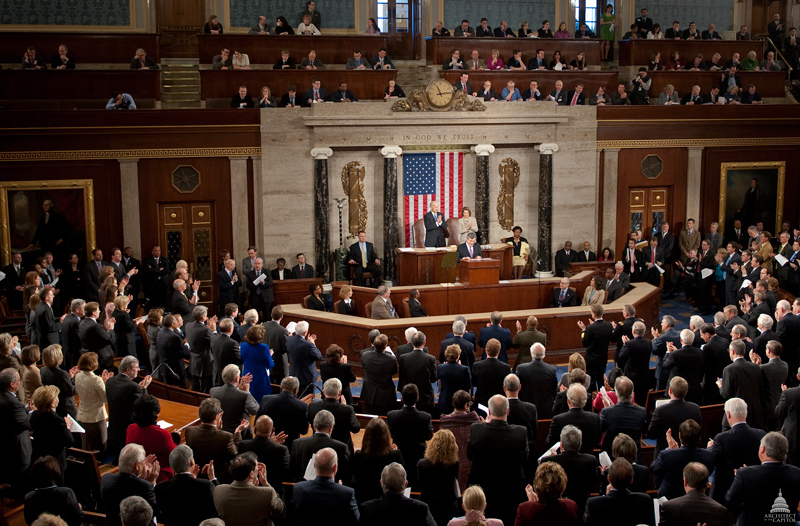

Representative Norm Dicks is retiring after 18 terms in the House.

Dicks was the Ranking Member (i.e. top Democrat) on the House Appropriations Committee and also the Ranking Member of the Committee’s Subcommittee on Defense. Consequently, his retirement announcement has led to significant speculation about who will become the top Democrat on the Appropriations committee, as well as what effect his retirement (and the announced retirements of two other high-ranking Committee Democrats, Reps. Olver and Hinchey) will have on the top spots on the subcommittees. This seems like as good a time as any to review the way the Democrats choose subcommittee chairs on House Appropriations, because not only is it a unique process among all congressional committees, but it’s also an absolutely fascinating institutional design.

I cannot emphasize this enough: gaming out the strategic implications of the Democratic Appropriations subcommittee selection process is mind-bending, almost begging for some SABRmetric-style clarity. It simultaneously resembles a professional sports draft, a strategy-based board game, and a missing-information game like poker. It’s awesome. It’s also ripe pickings for anyone looking to write an interesting political science paper (it’s on my list, but feel free to beat me to it; this blog post will give you the roadmap.)

Let’s do this Q&A-style, since it gets a little complicated. But bear with me, it’s worth it. We’ll start from the beginning — general selection of committee chairs — and work our way down from there.

Q. I thought there was a seniority system for committees? Isn’t determining the full committee Ranking simply a matter of looking at the seniority list of the Committee Democrats, and seeing that Rep. Kaptur is the most senior Democrat after Rep. Dicks?

A. Nope. Under the rules of the Democratic Caucus, the caucus nominates the chair/ranking of the committee, and seniority is only one factor taken into consideration. There are a bunch of other factors written into the rules, and of course there are politics involved as well. The GOP does it a similar way.

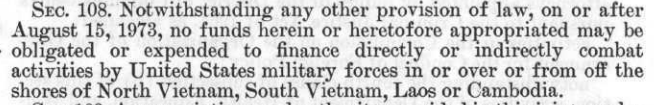

These party rules are different from the Rules of the House of Representatives, which are chamber rules approved by a majority of Representatives. The party rules are approved by the caucus/conference, and deal with internal party issues, although in some ways they end up structuring the House of Representatives much like the Rules of the House.

BTW, if you want to learn more about the caucuses and caucus rules in general, check out my old post on them.

Q. What do you mean “nominates”?

A. Under House Rule X, clause 5, most committee assignments are actually made by various House resolutions at the beginning of each Congress (for example, H.Res. 31 from the 112th Congress), based on nominations submitted by the caucus. This is pro forma, but illustrates the way the formal actions of the floor are intertwined with the off-floor actions of the caucus/conference.

Q. So how, specifically, are the committee chairs nominated in the Democratic caucus?

A. In the House Democratic Caucus, all standing committee chairmen except Rules, Budget, and House Administration are nominated by the Democratic Steering and Policy Committee (DSPC) from among the Members of the Standing Committee, and the nomination is submitted to the caucus for a vote. The DSPC is instructed by the rules to consider merit, length of service on the committee, commitment to the Democratic agenda, and the diversity of the caucus in making its nomination. If they nominate the Member of the standing committee with the most seniority, then by rule the caucus votes only on approval or disapproval of the nomination. If the DSPC nominates someone other than the most senior Member of the standing committee, then alternative nominations can be made within the caucus and, following debate, a secret-ballot election is held within the caucus for the nomination.

Q. Who’s on the DSPC?

A. The party leader (Speaker/minority leader) and other leadership Members, caucus leadership Members, and a number of others set by rule: a freshmen Member, 12 regional representatives, the Chair/Ranking of several committees, and up to 15 at-large Members chosen by the party leader.

Q. You mentioned that a standing committee Chair/Ranking was nominated by the DSPC from among the Members of the standing committee. How are they chosen?

A. Much the same way. The DSPC recommends Members for committees, and the nominated slates are ratified by the caucus. There are specific rules that guarantee all Members at least one assignment, and that prohibit Members from holding multiple high-value committee slots.

Q. Great. And that’s the same for Appropriations as the other committees?

A. Yes, except as noted above, there’s an alternate provisions for Rules, Budget, and House Administration, which give the leadership more power relative to the caucus as a whole in the case of Rules and House Administration, and less power in the case of Budget.

Q. So how do the House Democrats select subcommittee chairs/rankings?

A. For all committees except Appropriations, the rules specify that at the initial committee caucus organizing meeting, all Members of the committee caucus have the right to bid, in order of seniority on the full committee, for the chair/ranking of the subcommittees. So they more or less call the roll at the meeting, and Members pick what they want. Three of the committees — Energy and Commerce, Financial Services, and Ways and Means — are also required to have the winning bidders submitted to the DSPC and the full caucus for approval. The other committees do not require approval.

Q. What about the rest of the subcommittee Members?

A. After the chairs/rankings are decided for all subcommittees, the bidding process at the committee caucus continues. Everyone who hasn’t won a subcommittee chair/ranking gets to then, in order of full committee seniority, either “protect” a subcommittee they were on in the previous Congress, or to “pitch it in.” Once all Members of the committee have announced either what they are protecting or that they are pitching it in, then bids are made for subcommittee slots, based on (A) how many assignments you already have (either 1 or none, depending on whether you protected something) and then (B) your full committee seniority. The bidding continues until all subcommittees are filled. So if you were on the Subcommittee on Baseball last Congress, but you also want to get on the Subcommittee on Football this year, you have a choice: protect Baseball and hope that Football is still available in the second round of the draft, or pitch Baseball in, get a first round pick to use on Football, and then hope Baseball is still around in the second round. (Obviously, if there aren’t enough subcommittee seats for people to hold more than one, you have to choose Baseball or Football right out of the gate.)

In effect, the first round of picks ends up going like this: existing Members who pitched in by seniority, followed by new committee Members by seniority (since none of them have anything to pitch). The second round (if it exists) ends up going like this: the subcommittee chairs/ranking (they already had a round 1 assignment), followed by existing Members by seniority (which now includes all Members who protected), followed by new committee Members. So if you are a low ranking existing committee Member, pitching in your opportunity to protect an assignment can move you very far up the list in an effort toward getting a new subcommittee: you can often go from late in the 2nd round to early in the first.

All of this is governed by the Democratic Caucus rules. The GOP system is less centralized, but most committees using a similar bidding system.

Q. Ok. That sounds kind of fun. How is it different on Appropriations?

A. Three simple differences: first, the subcommittee chairs are not chosen by full committee seniority, but instead by subcommittee seniority. In other words, there’s no draft for subcommittee chairs/rankings. It just automatically goes to the most senior Member of the subcommittee who protects that committee (or chooses it first if no one protected it). Second, you can protect up to 2 existing subcommittee assignments when it’s time to protect or pitch in. Third, by House Rules, Appropriations can have more subcommittees (there are currently 12), and therefore, most Members are on there subcommittees when their party is in the majority.

If you brain has not started to spin, the ramifications probably haven’t clicked in yet. If they have, you probably have a huge smile on your face. Either way, read on.

Q. I’m not seeing it?

A. Well, the use of subcommittee seniority instead of full committee seniority has three massive strategic implications. First, there’s a lot of value in staying on a less popular or less desirable subcommittee; less-senior Members of the full committee can quickly get subcommittee seniority. Second, there’s a trade-off that has to be weighed between being a chair/ranking of a lesser subcommittee and being a junior Member of a powerful subcommittee. Would you rather be the chair of the Legislative Branch Subcommittee, or a junior Member of the Defense Subcommittee? Finally, the subcommittee seniority system makes it dangerous to test the waters at the selection process. As soon as you pitch in a subcommittee, you lose all seniority on that subcommittee — even if you get back on it by picking it in a later round of bidding. And picking a subcommittee earlier than someone else in the same draft gives you the seniority.

These issues simply don’t present themselves on the other committees: to become a subcommittee chair, you just have to wait until you have the full committee seniority, you can’t gain advantage by squatting. Nor can you lose it. As we will see, it also turns out that we can use the unique appropriations committee process to empirically estimate the perceived value of different subcommittees. But we have to solve a logic puzzle first. (more on that later.)

Q. Ok. I’m still not sure I see it. Walk me through it.

A. Ok. It’s the committee caucus meeting. When the Democrats are in the majority, most returning Members will have three existing subcommittee assignments.We call the roll in full committee seniority order. Each Member can protect up to two of the existing assignments, or pitch any number of them in. New committee Members will obviously have nothing to pitch in.

Once we get through the whole roll, we’ll have two things: a board that shows what slots have been protected on each subcommittee and how many additional slots are available, as well as a three-round draft order. The draft order will look like this:

Round 1: Everyone who either pitched in two assignments, or is new to the committee, in order of seniority

Round 2: Everyone from round one, plus everyone who pitched in one assignment, in order of seniority

Round 3: Everyone on the whole committee, in order of seniority

Q. Ok. I think I get it. But why is it fascinating?

A. Mostly because Members are put in the position of having to make very important strategic choices with very little time to consider the implications. All information about pitching in and protecting is public, but it’s not made public until the very moment it happens, meaning you might not have a full understanding of the draft order ahead of you until seconds before you have to choose whether to pitch in both of your assignments. Nor will you ever know for certain the priorities of those ahead of you, or the actions that will be taken behind you in the draft. And those pieces of information are vital if you want to maximize your protections and picks. I’m convinced that many Members do not maximize their utility in the draft.

Here’s a simple example: say we’re having an approps assignment draft, and the only changes to the membership of the committee is that two members have retired: a Member of the Defense Subcommittee and a Member of the State-Foreign Ops Subcommittee. Two new Members have been added to the committee. You are currently chair of Legislative Branch, but you’d really like to get on Defense, and you are willing to give up the gavel on Leg Branch for it, but you really don’t want to give up the Leg Branch gavel and not get the Defense slot. And you really don’t care about State-Foreign Ops.

When it’s time to pitch in, everyone more senior than you protects 2 assignments (meaning they don’t have a first round pick), except for one person, who pitches both of their assignments, meaning they can have Defense if they want it. But you think they want State-Foreign Ops. But when you asked about it before the meeting, they were coy. And you know they are really good friends with the person directly behind you in seniority, and you know that Member wants Defense.

It’s now your turn. Do you pitch in both assignments, knowing that once you do, you can’t get back the chair on Leg Branch? But what if you don’t pitch them in, and then the person ahead of you takes SFO, leaving Defense to pass you by?

It’s a dilemma.

Q. Neat. Is that all?

A. Not by a longshot. Remember, the whole process cascades. If you pitch in Leg Branch, that means that whoever was second in seniority on Leg will now be the chair if they protect it, which obviously affects their strategic calculations. And possibly their lobbying efforts for what you should do. And dare we say their information sharing? Furthermore, openings in committees that you have no interest in can severely affect your fortunes, since they can strongly affect the cascade if seats open up on popular committees, and mid-range committees are left with only the chair protecting them, which is often the case in a full-draft at the beginning of a Congress. And yes, Members and staffers do think about these things.

Q. So that’s kind of cool, but is that all?

A. Nope. Because once we (as observers) have the draft order and the picks, all sorts of interesting things can be observed. First, it gives us a great measure of the relative desirability of the subcommittees, since we can see what draft picks were used to get what slots. Second, it lets you understand some of the individual Member politics, since you can observe Members using high picks to lock-up slots that ex ante don’t seem that desirable. And finally, it lets you see if Members made mistakes, or at least bad value plays like the Oakland Raiders make in the NFL draft. For instance, if a Member uses a first round pick to get a slot (say, third most senior Member of Subcommittee X, which has five slots), and that exact slot is still available when the Member makes their second-round pick, it’s pretty obvious that the first-round pick was either super risk-averse (since there was plenty of buffer to just get on the subcommittee) or a lot of wasted value.

Q. So, where can we look at the old drafts?

A. You can’t. The drafts are held closed-door, and neither the pitch list or draft order is released. Just the final results of the selection process.

Q. Oh, come on.

A. Don’t worry: there’s a way to recreate the drafts, using nothing more than basic logic. If you examine the subcommittee rosters before and after a draft, you can deduce certain things using two principles:

1. Among senior subcommittee Members, when the seniority order does not change from before to after a draft, that implies (but doesn’t prove) a protected slot.

2. When a less-senior (by full-committee) Member appears ahead of a more senior Member, it proves the selection was made in a previous round of bidding.

These two principles allow us to often be able to recreate the full draft. Here’s a quick example, using a hypothetical subcommittee in which the Democrats are going from 5 to 8 seats, because they have reclaimed the majority:

Here’s how you back-out information about the draft order. We can see that Buchanan and Lincoln pitched this subcommittee. We can also see that Roosevelt must have pitched it too (only to get back on later), since otherwise he would be at least ahead of Carter, Bush, and Clinton, as they weren’t previously on the subcommittee. We can also be almost certain that Adams and Jefferson both protected the subcommittee, because if Adams didn’t, then Jefferson could have become chair simply by protecting it; likewise, if Jefferson didn’t, Buchanan would have had the same opportunity, as would have Roosevelt. Since that didn’t happen, it’s almost a lock that what did happen was that Adams protected it and so did Jefferson. We also know that Ford picked the subcommittee in a later round than Carter, Bush, and Clinton, since he has a higher full committee seniority but a lower seniority on the subcommittee.

Doing this kind of logic puzzle across all subcommittees will eventually yield the protected subcommittees, the draft order, and the actually draft picks of all Members. It takes a few minutes and you definitely need pencil and paper, but it’s actually kind of fun. I suppose it’s theoretically possible that a situation could arise in which some information can’t be known for certain, but I’ve done a handful of them and each of them has been fully solvable.

Q. What do the draft picks tell us about the committee?

A. Below is an example draft from the past, with the protections and draft-order picks (but not the third item we could generate: a 3-round draft order with Member names attached). This is from a year that the number of subcommittee seats was greatly increased, due to power transfer. Using the technique above, I backed-out the protections, the draft order, and the draft picks.

In this draft, there were 35 Members of the full committee (24 returning and 11 committee freshmen). Thirteen returning Members protected two seats, five protected one seat, and six protected no seats. So picks #1-17 were first round picks (the five no-protects plus the freshmen), picks #18-39 were second round picks (the 11 no or one-protects plus the freshmen), and picks #40-68 were third round picks (everyone, except there not quite enough seats for all to have a third subcommittee).

| Defense (9 slots) |

|

[P] |

[P] |

[P] |

[P] |

[P] |

2 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

| Labor/H (11) |

|

[P] |

[P] |

[P] |

[P] |

[P] |

[P] |

7 |

8 |

10 |

11 |

13 |

| Energy and Water (9) |

|

[P] |

[P] |

[P] |

[P] |

25 |

34 |

35 |

45 |

48 |

|

|

| Transportation (8) |

|

[P] |

[P] |

17 |

18 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

28 |

|

|

|

| State / Foreign-Ops (8) |

|

[P] |

[P] |

9 |

12 |

15 |

26 |

29 |

33 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CJS(8) |

|

[P] |

[P] |

[P] |

14 |

31 |

32 |

46 |

50 |

|

|

|

| Interior (8) |

|

[P] |

[P] |

[P] |

[P] |

[P] |

30 |

37 |

49 |

|

|

|

| Agriculture (8) |

|

[P] |

[P] |

[P] |

24 |

27 |

42 |

57 |

61 |

|

|

|

| Homeland (9) |

|

[P] |

19 |

23 |

38 |

44 |

51 |

55 |

56 |

60 |

|

|

| Military Construction (8) |

[P] |

[P] |

40 |

41 |

53 |

59 |

62 |

63 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Financial (8) |

|

1 |

3 |

36 |

38 |

43 |

52 |

54 |

66 |

|

|

|

| Leg Branch (6) |

|

16 |

64 |

65 |

67 |

68 |

69 |

|

|

|

|

|

A few things to note about this:

1. I’ve divided the subcommittees into three groups, based on how popular they were to protect, and how high their open seats went in the draft. It’s pretty clear that, from this draft, Defense and Labor/H were the most popular subcommittees among Democrats, and Financial Services and Leg Branch were the least popular. You can see that Defense and Labor/H were the most protected and the earliest picked; in fact, every returning Member of those two subcommittees protected their seats, all the other picks are for new seats. After the first pick took the chair of Financial Services, 9 of the next 11 picks went to Defense or Labor/H.

Conversely, Financial Services and Legislative Branch were not protected by anybody. That’s right: every existing Member of those subcommittees could have been the chair, but opted not to be. Now, in some cases the Member might have already been the chair of another subcommittee (you can only hold one), but in many cases this is not the case — people simply value a back-bench seat on Defense, Labor/H, or SFO more than a gavel on Leg Branch. That allowed the 16th pick to get the chair, and the 16th pick in the first round will always be quite far down the full committee seniority list, since protecting even one slot means you don’t have a first round pick. The only people who can pick in the first round are those who have pitched in everything, and the committee freshmen.

2. There appears to be one very strange pick, and that’s the #3 pick taking Financial Services. It’s odd because the pick could have been used elsewhere and the same seat been had during the second round (the Member with pick #3 also had second-round pick #23).

Q. Why are the subcommittee chairmanships so valuable?

A. Influence over policy, which leads to influence over politics. And also resources (staff, offices, etc.). In the world of subcommittees, the chairs tend to dominate. It’s really their show. And they are called cardinals, ahem.

Q. Are there external factors that influence how people pick and how the draft goes?

A. Sure. One issue is the size of the subcommittees. The number of seats can obviously vary, and the majority party has strong control over the number. Therefore, accommodations can theoretically be made if more Members are interested in a subcommittee than there are available seats. It’s not clear how common this is.

Second, the party chamber leadership almost certainly has an interest in who chairs the subcommittees, and may wield that influence prior to the draft. In any case, they have a strong say, because the subcommittee chairs are subject to approval by the DSPC and the caucus.

Q. They are?

A. Yes, just as with the Energy and Commerce, Financial Services, and Ways and Means committees, the subcommittee chairs of Appropriations are subject to a vote in the DSPC and the caucus. It is not at all common for them to be rejected by either body.

Q. So no one else does it this way?

A. Nope. The GOP uses a less-formal system in general for subcommittee assignment, and they don’t differentiate betweeen Appropriations and other committees. Ditto with the Senate. The House Dems are the only ones who use a formal subcomittee-seniority system.

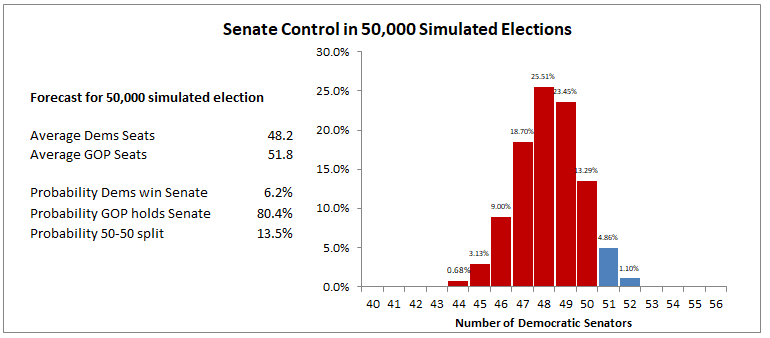

Q. When does all this go down?

A. Not until after the election and the start of the new Congress. The committee caucus can’t meet until the Members of the Committee are chosen, and they can’t be chosen until the election tells us who’s in Congress. Both parties usually convene in the weeks after the November congressional elections to hold the initial caucus meeting, at which they usually adopt rules and select leaders and work such things out. If there’s a sudden opening due to resignation or death, then a draft is held mid-session, after the new Member of the committee is named. But those drafts are less interesting, because there are, naturally, only a few open slots on subcommittees.

Previous “Q&A” style posts

March 2, 2012 — Filling the tree in the Senate.

December 15, 2011 — Rule Layover Waivers in the House.

December 5, 2011 — How a bill becomes a law. Literally.

November 29, 2011 — The other caucuses. The ones in Congress.